Some thoughts on Guardians of the Galaxy Vol 3

What does the screenwriter want?

What does the screenwriter want?

The screenwriter wants to get into the room with The Person Who Can Say Yes.That is the only thing that matters. Everything before that is preliminary, and, often, a complete waste of time for everyone involved.

Here is a typical scenario:A producer has optioned a piece of IP. It could be a book, a graphic novel, a Twitter account, a board game, a toy, a sticker, a photograph, anything. The producer, also, wants only to get into the room with The Person Who Can Say Yes.The Person Who Can Say Yes is someone high up in the studio food chain, someone who has been authorized to spend money to hire writers. There are very few in Hollywood, and they wield enormous power.

The Person Who Can Say Yes wants only one thing: to keep their job. Because they wield such enormous power, every other executive around them, at their studio and other studios, is constantly trying to get them fired so that they might take their job and wield that power. But that’s a subject for another time.

Between the screenwriter and The Person Who Can Say Yes are lots and lots of other people. Producers, lower-ranking studio executives, development executives, story executives, and unpaid interns, all of whom wield more power than the screenwriter.

To say nothing of the screenwriter’s representatives, who have their own agenda unrelated to the writer getting into the room with the Person Who Can Say Yes.

So the producer has a piece of IP. The producer also knows some screenwriters. That, essentially, is what a producer does: they know people. They own a phone, and a car, and they know people. Those are the only requirements for being a producer.The producer calls the screenwriter’s representatives and says “I have this piece of IP and I think your client would be a good match for adapting it for the big screen.” The screenwriter’s representatives then call up the screenwriter and breathlessly exclaim, “Big Important Producer has obtained the rights to Hugely Popular IP and he wants YOU to adapt it!”

The screenwriter can then say “Eh, that doesn’t really sound like a good idea,” or they can say “Wow, Big Important Producer wants ME to adapt Hugely Popular IP? I can’t wait to meet them!”

Maybe the producer DOES want the screenwriter to adapt it, and maybe the producer has called a dozen different screenwriters’ representatives and told them all the same thing. It would certainly make sense to do so, since some might say no and some might say yes and then fail to come up with any ideas.So the screenwriter meets the producer and they talk about the idea. The producer may have specific goals in mind for the IP, or they may have specific ideas about casting or directors or whatnot, and they’ll ask the screenwriter to incorporate those ideas into their pitch. Then they’ll set a meeting for the pitch.

So the screenwriter has to come up with a pitch. The screenwriter hasn’t been paid anything to come up with a pitch. The screenwriter doesn’t have the power to say “No, I’m not going to write a pitch for you, put me in the room with The Person Who Can Say Yes.” If the screenwriter did say that, that would be the end of his relationship with the producer, who controls the IP. The producer, like the screenwriter, wants only to get into the room with The Person Who Can Say Yes, but they’re not going to go into that room without knowing what they’re pitching, because they only get once chance to pitch to each Person Who Can Say Yes, and there are very, very few People Who Can Say Yes in Hollywood.

So the producer tells the screenwriter to develop a pitch and get back to them.

What does the pitch entail? Basically, it’s the story of the movie. Beginning, middle and end. The three acts. What does the protagonist want, what do they do to pursue their goal, what stands in their way, how do they prevail, etc. By the end of Act I, the protagonist must be headed toward their goal. By the middle of Act II, they must have a “false victory” that makes it look like they’ve got it made. By the end of Act II they must suffer a fate that makes it look as though they will never achieve their goal, and by the end of Act III they must achieve their goal or else they must fail in a way that makes the audience feel good.

So the screenwriter sketches all that out. It doesn’t sound like a lot, does it? And yet, that’s the whole movie.

So the screenwriter pitches the story to the producer, who inevitably says “I need to know more.” They need to hear the “trailer moments,” the scenes that will hook an audience into the story. They need to know the twists that will come out of nowhere and yet seem inevitable, they need to know the last-minute reveal that will shift the paradigm of the narrative. They need to present to the Person Who Can Say Yes the entire narrative of the movie.

Now the screenwriter has another choice. They can say “No, you’re asking me to write the whole movie for free and that’s abusive,” but that would end their relationship with the producer, who will never work with the screenwriter again because the screenwriter is “difficult.” The screenwriter has spent maybe a week of their life at this point working on breaking the story, but the producer likes what they’ve heard so far, why not fill in some details?So the screenwriter spends another week writing a treatment, and then there’s another meeting with the producer, where the screenwriter pitches the entire movie to the producer: all the major scenes, all the twists, all the aspects of the narrative that will hook an audience. The producer loves what the screenwriter has done, but “has some notes.” The producer confers with his assistants and unpaid interns and they put together a list of notes that they want the screenwriter to address. And, also, as long as the screenwriter has a whole treatment written, can they see that treatment so they can understand the story better?

All of this is against the rules of the WGA. And it happens ten thousand times a day in Hollywood.

So the screenwriter does another draft of a treatment for the producer. And another. And another. What choice do they have? Nothing else will get them into the room with The Person Who Can Say Yes.

Now, maybe six months have passed. The screenwriter has produced maybe ten drafts of a treatment for the producer. Every scene in the movie has now been outlined.Now, remember, the screenwriter, statistically, has no money, and has no hope of money without selling a pitch, so, in order to stand a chance of selling something to anyone, they have to have a dozen or so different projects going on at once, in different stages of development, all before they can ever get into the room with any Person Who Can Say Yes. Some of the projects will be dear to the screenwriter, some will be for movies that the screenwriter would never even want to go see, much less write. Some of the projects are with people the screenwriter enjoys working with, some are with abusive assholes who like to bully and mind-fuck people. The abusive assholes tend to get more projects made, hence their attractiveness to screenwriters.

Sometimes, for an especially high-profile piece of IP, or for an especially high-powered producer, the screenwriter’s representatives will get in on the action, demanding to read the treatments and presenting their own notes, which the screenwriter has to then incorporate into the pitch or else run the risk of alienating their representatives.The producer then takes the screenwriter to the studio, and meets with someone high up in the production chain, and the screenwriter pitches the entire movie to that development executive.

The development executive then says “I love it, let’s take it to the Person Who Can Say Yes” but, yes, before that happens, has some notes.

So the screenwriter now, again, has a choice. They can say “Fuck you, it’s been six months of me working without getting paid, I’m not working on this project for one more second without a substantial paycheck,” but then that would end their relationship with the producer and the studio executive and the studio itself. So the screenwriter says “Yes, I’d love to hear your notes,” and the development executive says “Would you mind if we took a look at your treatment? It would really help us focus our notes.”And the screenwriter turns over their treatment, and the development executive and their assistants and unpaid interns get together and put together a list of notes.

This might go on for another six months, as the development executive asks for more and more changes. And then the development executive might want to show the pitch to ANOTHER development executive, so the screenwriter and producer will have to pitch to that development executive too, and so forth. Maybe a year into the process, maybe longer (my record is two years) the big day arrives, and the screenwriter, the producer, the producer’s assistants and unpaid interns, the development executives and assistants and unpaid interns, all meet at the studio with the Person Who Can Say Yes, who has their own platoon of assistants and unpaid interns.

The producer then sets up the pitch, tells the Person Who Can Say Yes why the project is commercially viable, and then turns to the screenwriter and says “And here’s the screenwriter, who will now pitch you their ideas.” No one else in the room ever, ever, ever steps forward and says “We’re really proud and excited about this pitch that we all contributed to,” because if the Person Who Can Say Yes says no, they’re all in danger of losing their jobs. So everyone in the room who has given notes to the screenwriter and has followed every step of the process behaves as though all this is brand new to them.The screenwriter then does the pitch. The pitch must be delivered with the creativity, dynamism and force of a $200 million dollar spectacle. It must feel to the Person Who Can Say Yes that they’re seeing the whole movie there in there office.

The Person Who Can Say Yes then, usually, says no, for any number of reasons. Maybe they said yes to a similar project the day before, maybe they’re mad at the producer for some reason unrelated to the project, maybe their third-quarter projections aren’t hitting their mark and they’re afraid they’ll lose their job if they start a project like the one the producer has brought in, or maybe they don’t like the pitch. And sometimes the Person Who Can Say Yes says “I like it, but I have some notes,” and the screenwriter, once again, has a choice to make. They’ve come this far, they’ve spent a year and a half on the project, all without pay, but here they are with the Person Who Can Say Yes and the Person Who Can Say Yes has not said “No.” The big paycheck is dangling in front of them, what is the screenwriter supposed to say?

The screenwriter might go to their representatives and say “What am I supposed to do, I can’t pay rent and I’ve been working on this project for a year and a half and they’re not paying me anything, and the screenwriter’s representatives will say “Do the extra work for free,” because, here’s a secret, the screenwriter’s representatives don’t represent the screenwriter, they represent the Person Who Can Say Yes. Why? Because the People Who Can Say Yes control the entire Hollywood economy, and if an agent or manager demands something from them, the People Who Can Say Yes won’t hire that person’s clients anymore.

Anyway, that’s just one tiny aspect of what the WGA is up against in this strike, and it was my day-to-day reality for 25 years.

The first time the WGA changed my life

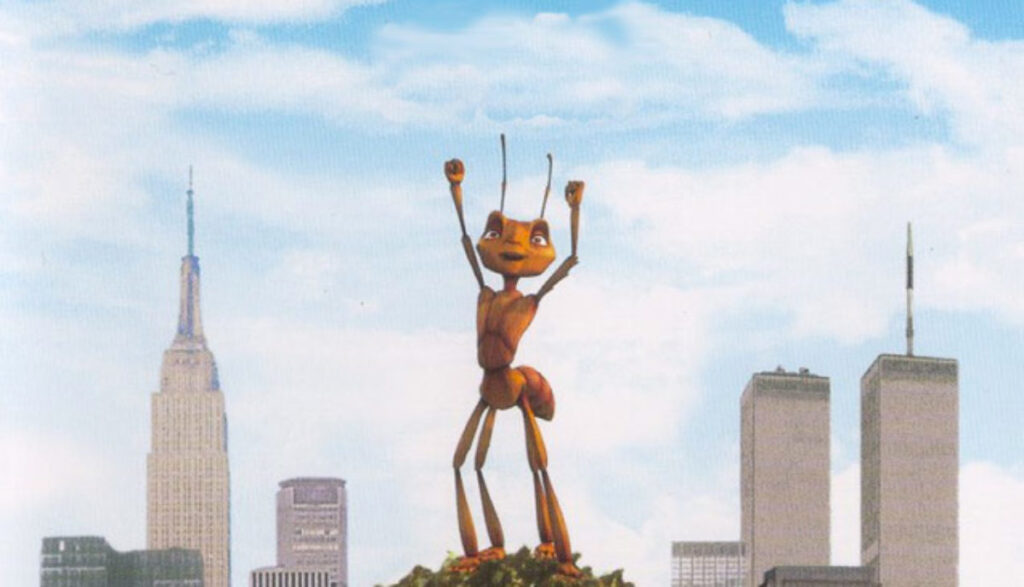

In the summer of 1995, a studio executive at Dreamworks, Nina Jacobson, read a script of mine that had gotten some attention in Hollywood, and had a meeting with me in New York. We got along great and, months later, she called me up with an unusual question: would I like to write an animated movie about talking ants?

I had never written an animated movie before, and didn’t really consider it my “area.” I was a “downtown playwright” living in a crappy apartment on 12th St in Manhattan, where prostitutes regularly waited for clients. I was “edgy.” I wrote plays about serial killers and psychic phenomena. But, I reasoned, if I was going to write an animated movie, it might as well be for Jeffrey Katzenberg, the man who had spearheaded the Disney Renaissance with the movies The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, and a little bauble called The Lion King.

Nina flew me to Hollywood and treated me very, very well. Everyone at Dreamworks treated me very, very well. I got to meet Steven Spielberg, who gushed to me about how much he loved the screenplay that had gotten Nina’s attention, a moment that I will cherish forever.

Most importantly, I got to take a master class in screenwriting, directly from Jeffrey Katzenberg, who had no patience for any writer’s indulgences beyond “WHAT DOES THE GUY WANT?” a phrase he reiterated so often, I wrote it down on a postcard and stuck it over my desk. Because, after all, that is, in fact, the only question a screenwriter should ever be asking, or answering: What does the guy (ie, the protagonist) want?

It wasn’t easy, going from being a smartass downtown playwright to efficient Hollywood scribe, and, looking back on those days, I’m consistently amazed at how well I was treated by the entire staff of the studio, how patient and kind they were to a screenwriter who, literally, didn’t understand the first thing about writing screenplays.

The early days of writing the script for Antz went like this: Nina and I would meet in the morning, talk through the story, and then I’d go write a treatment based on the conversation we’d had. When Nina felt like the story was good enough to take to Jeffrey, we’d have a meeting in his office, or we’d have a meeting with Walter and Laurie Parkes, who were also higher-ups in the Dreamworks production team. Jeffrey, or Walter and Laurie, would listen to the story and give us notes, and then Nina and I would talk over the notes, and then I’d write another treatment.

There would be occasional guest stars. The wonderful screenwriter Zak Penn had been hired on a consultant on the script (Nina had asked Zak to write the script before me, but he was busy working on another project). Zak was a big deal at the time, and was also extremely kind and patient with me as I fumbled my way through the development process. The great writing team Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio were on the staff of Dreamworks at the time as sort of free-floating story doctors, and they were also extremely kind and patient with me, sharing their wisdom and humor freely with me. Steven Spielberg sat in on a story meeting at one point and offered his own take on the material. And there were other Dreamworks executives and producers who weighed in on various aspects of the story. To say nothing of the visual consultants who were hired to create vision boards to help me in getting a better picture of the movie I was writing.

In all, I wrote 30 treatments for Antz before being given the green light to write the script. Some of those treatments were as short as two pages or as long as forty.

I was paid for none of them. Those treatments that I wrote over months of development were all just part of the audition process, the same audition process that any writer has to go through in Hollywood in order to get a job writing a screenplay.

I didn’t care, of course, I was a smartass downtown playwright who was staying at the Chateau Marmont, being fed every day by Steven Spielberg’s personal chef, dining at Beverly Hills restaurants with some of the most powerful people in the industry and having an amazing time. The studio even flew me to Chicago for a weekend because I was doing my one-man show there. They showed me nothing but respect and affection.

The day finally came, after about six months of work, that Jeffrey listened to my pitch, said “Yep, that’s it,” and then purchased, for $40 million, an entire animation studio in Palo Alto, and then put me on David Geffen’s private jet to go meet with the directors and dozens of animators who were working to bring my cinematic notions to life.

All very head-spinning stuff for a smartass downtown playwright!I was finally formally hired to write two drafts of a screenplay. I only wrote one, but they paid my contract in full. They then hired Chris and Paul Weitz, an up-and-coming screenwriting brother team, to take over for me. Chris and Paul, I should also note, were ALSO very kind to me, and were cheerful, solicitous and complimentary colleagues for the time we worked together. Chris and Paul, of course, went on to write and direct many, many fine motion pictures.

I didn’t mind being replaced on Antz. Writers in Hollywood get replaced all the time, for a variety of reasons, there’s no reason to take it personally.

Shortly before the movie opened, Nina called me to tell me that the Weitz brothers’ representatives had contacted the studio to alert them that they were seeking to have my name removed from the credits for Antz. It’s easy to see their logic: I had worked on the script for six months, and they had worked on it for two years. What’s more, they had personally worked alongside the directors and animators to best present the most coherent version of the material possible. They had worked hard on the movie, and they felt a sense of ownership. I can’t blame them, I would have too!

Jeffrey Katzenberg, to his everlasting credit, told the Weitz’s reps that, yes, their clients were welcome to challenge the studio’s credit assignment. However, although the movie was animated, and therefore did not fall under the jurisdiction of the WGA, the studio would hire a WGA arbitrator to arbitrate the credit assignment according to WGA rules.

At that point, the Weitz’s reps dropped the complaint and the movie came out with my credit intact. Because, under the arbitration rules of the WGA, they ran the risk of having THEIR names, not mine, removed from the credits. Because the WGA values, above all, the work that the first writer does. Whoever comes after the first writer of a screenplay faces significant hurdles in trying to claim the work as solely their own, under the rules of the WGA.

Just as I did not want to see my credit taken off Antz, I also did not want to see the Weitz’s credit taken off either. They did an incredible amount of work, and under the pressure of a deadline, with a million moving parts churning all around them. My hat’s off to them and all the other people who made the movie what it is. There are no villains here. But without the WGA, I would not have the one hit-movie credit I do.

Of course, I receive no residuals from Antz, because, being animated, it does not fall under the jurisdiction of the WGA.