Venture Bros: Showdown at Cremation Creek, Part II

Everyone needs a story; it’s how we define ourselves. Our lives are meaningless without a narrative to transform them. Without a narrative, a human life is seventy years of haphazard coincidences. With a narrative, they become poetry, drenched in meaning and drama.

Some people take this idea further than others.

In this concluding episode, David Bowie fulfills his promise as a symbol of transformation. He transforms all over the place in this episode — into Iggy Pop, Dr. Girlfriend, an eagle, a pack of cigarettes. In real life, Bowie took the idea of narrative as a transformative device to baroque extremes, creating a new persona with each new album. It’s difficult, I imagine, for a modern audience to understand how audacious and exciting this was back then. Madonna puts on a new hat with each of her reinventions, but for her it feels more like a marketing decision, a way to keep the old perpetually new. With Bowie, the transformation was the subject of his art itself. And what’s more, he transformed himself every year for 15 years or more, a decision that would make today’s marketing executives shudder in horror; no sooner would he acquire an audience but would then shed it immediately the next album (or, famously in one instance, even in the middle of the tour promoting the current album/persona). Now he has settled in to his still-current permanent persona of “David Bowie,” classy British guy with a reputation for brilliance. (How ironic that Bowie’s most recent album is titled Reality.)

The woman he’s giving away, Dr. Girlfriend, comes all this way without finally transforming herself: she pointedly never gets to say “I do” to The Monarch. She hasn’t completed the commitment ceremony, she’s still the woman of a half-dozen costumes and personas. Would that make her spiritual father Bowie happy, or would he be saddened to know that his spiritual daughter hasn’t yet found herself, is still gathering meaningless personas, is still, in essence, pretending to be something she’s not? Lady Au Pair, Queen Etheria, Dr. Girlfriend? Who is she, finally? Who could she be if she can’t even settle on a narrative to define her life? If she’s not careful, life will decide her narrative for her.

That is, after all, what has happened to Dr. Venture. He’s decided that narrative is for babies. Burned by narrative at an early age, he’s thrown it on the trash heap and decided to face life on its own terms. As a result, he is in control of nothing in his life. He has no ideas, he’s haunted by the ghost of his father, he’s dominated by his twin brother. In this episode, while everyone else is busy heroically pursuing their narratives, he gripes, carps and eats a sandwich. Thrust into an actual heroic journey, Dr. Venture can only retreat into the most mundane details of life.

(A friend of mine once told me that, in psychoanalytical terms, one has until age 30 to decide who one is. After that, one is stuck, reinvention is impossible. This is how we know that Elvis Presley is dead — one cannot crave wealth and fame for 23 years and then, at age 42, decide one does not care for them after all.) (Elvis Presley — speaking of people who live their life according to an invented narrative — his being Dr. Faustus.)

But look at Dr. Girlfriend’s boyfriend, The Monarch. He has chosen the butterfly, the ultimate symbol of transformation, as his narrative device (which he calls “a theme thing”). Who knows, after all, if his absurd story of being raised by butterflies (back in Season 1) is true or not? It must have seemed true to him at the time; in any case, he’s picked his narrative and he’s sticking by it, regardless of the apparent inconsistencies and the scorn his decision brings. (If The Monarch and Dr. Girlfriend have a baby, that baby’s lullaby can only be David Bowie’s “Kooks.”)

Brock, like Dr. Venture, doesn’t have time for pretense; he just wants to get on with it. Yet he has defined himself by another, more subtle narrative, that of the protector of the innocent. He transforms himself in this episode, donning the hated butterfly wings (Brock gets his wings; his tatoo of Icarus, ironically, does not), to do what, exactly? Not to protect Hank and Dean or Dr. Venture. Hank he only protects as an afterthought, Dean’s protection is left in Hank’s hands (“Am I my brother’s keeper?” quoth Cain) and Dr. Venture is left in the hands of his arch-enemy The Monarch.

(The Monarch, in a telling moment, when faced with certain death, invites Dr. Venture to escape with him. Why? Why not escape by himself and kill his arch-enemy? I’m guessing because, as I’ve said earlier, The Monarch defines himself by who he’s arching; without Dr. Venture, he’s nothing. This is borne out by the end of the show, where The Monarch gripes about Phantom Limb being his “new” arch-enemy — as though he would have it any other way.)

No, Brock drops all his obligations in order to rescue Dr. Girlfriend, the damsel in distress. This is, of course, one of the oldest narratives in existence, which could be why Brock falls back upon it when faced with a crisis.

It certainly explains what happens to poor Dean in this episode. Left alone in the engine room, filled with anxiety and feelings he cannot define or control, Dean conjures up the grandest narrative of all, involving a melange of “heroic journey” tropes, including a damsel in distress, a magic ring, a white, bearded deity, magical animals, enslaved innocents, an evil robot overlord and a giant flying dog. Why does he retreat into this bizarre, ridiculous narrative? Because otherwise his life has no meaning. This all comes out in the final moments of his delusion where he frees the enslaved orphans (symbol of his trapped innocence) and rants not about an evil robot overlord but about his own father and the absurdities heaped upon his young life, the monsters and yetis and evil scientists he must contend with every day. Dean’s “real life” makes no sense and he doesn’t have the tools to fashion a useful narrative for himself. Instead, he fashions an un-useful narrative as a weapon against his doubts and pain (and, interestingly, puts his father’s life in danger as a result). (How Dean manages to change from his butterfly outfit back into his street clothes is another question entirely.) (The dog-dragon, of course, is from The Neverending Story, in which a motherless boy, guess what, disappears into a narrative in order to deal with his grief.)

Meanwhile, Dr. Orpheus and co. have found themselves stuck against reality’s brick wall. How will he and the Order of the Triad rescue Hank and Dean, when Dr. Orpheus can’t even buckle his seatbelt? With the aid, of course, of a fictional character, a minor character from Star Wars, conjured not from the movie but from a trading card. The Alchemist worries that the creature is an abomination that should be killed; Dr. Orpheus opines that, whether the creature fictional or not, it is still a living thing. And, it turns out, their salvation. (Of course, no one in the Venture universe ever really learns the lessons they’ve been taught — no sooner are they rescued by a fictional character than they roll their eyes at Dean for retreating into a world of fantasy.)

The need for a narrative in life reaches its bleakest, most terminal point with the death of the Monarch henchman in Brock’s arms. Spitting blood onto Brock’s shoulder, he confesses that the time he’s spent under his command have been the finest of his life. This is, of course, the narrative that every soldier tells himself as he goes into battle, that his actions have meaning, that he’s risking his life for something meaningful and worthwhile — without it, what he’s doing, throwing his life away, is the ultimate in perversity. The soldier’s lie withers as his body is transformed into a hunk of meat, from a living thing to an object. And Brock, who has no use for pretense in the first place (or sentimentality for that matter), listens to the harmless lie, then uses the body to jam the engine of an approaching aircraft: finally, in death, the unknown soldier becomes useful.

(Or maybe I’m wrong; maybe the henchmen is sincere in his statement to Brock, maybe he finally has found meaning through serving under Brock — after all, one would have to have a pretty empty life indeed in order to find fulfillment dressed up as a butterfly.)

Hank wants that henchmen’s narrative so badly he can taste it. He disobeys Brock’s command to take care of Dean (“Why do you have to be the screen door on my submarine?” he pouts) and joins the henchmen’s fight. When faced with the reality of it, of course, he recoils in horror and screams like a little girl. Hank wants that narrative but in the end he doesn’t have the guts for it. (“Again, again!” he blurts after his near-death experience, clearly not understanding the meaning of the dying henchman’s story.*)

Henchmen 21 and 24 have long functioned as Shakespearean clowns in this show, speaking in malapropisms that nevertheless reveal theme and authorial intent. Here, they talk about a group of lost henchmen and reference the phenonmenon of the “urban myth,” underscoring humanity’s need to make up narratives out of thin air in order to deal with the chaos and absurdities of life.

Dean finds his purpose by recycling a heap of pop-culture detritus and fashioning it into a meaningful narrative. The Venture Bros does something quite similar, turning over bits of trash to find the wriggling, bleeding humanity underneath.

And it’s very funny.

*With the dying henchmen, and Brock’s treatment of him, I keep beingreminded of Snowden, the dying airman in the back of the plane in Catch-22. “Yossarian heard himself scream wildly as Snowden’s insides slithered down to the floor in a soggy pile and just kept dripping out…Yossarian screamed a second time and squeezed both hands over his eyes…He forced himself to look again. Here was God’s plenty, all right, he thought bitterly as he stared — liver, lungs, kidneys, ribs, stomach and bits of the stewed tomatoes Snowden had eaten that day for lunch…He felt goose pimples clacking all over him as he gazed down despondently at the grim secret Snowden had spilled all over the messy floor. It was easy to read the message in his entrails. Man was matter, that was Snowden’s secret. Drop him out a window and he’ll fall. Set fire to him and he’ll burn. Bury him and he’ll rot like other kinds of garbage. The spirit gone, man is garbage. That was Snowden’s secret.” And Snowden (and Yossarian) signed up to fight and die for one of the worst kinds of narratives, that which insisted that the United States was the handsome prince rescuing the princess of Liberty from the evil clutches of the Fascist overlords. Perhaps it all come back to David Bowie, who notes, in his song “Soul Love:”

“Soul love, she kneels before the grave

Her brave son, who gave his life to save a slogan

That hovers between the headstone and her eyes

For to penetrate her grieving.”

Venture Bros: Showdown at Cremation Creek, Part I

As this is the first half of a two-part episode, any attempts at analysis are bound to be premature. But what the hell.

The theme tonight seems to be “commitment.” In the A story, Dr. Girlfriend wants a commitment from The Monarch, while in the B story, Dr. Orpheus wants a commitment from The Alchemist. The Monarch submits to Dr. Girlfriend’s desire, The Alchemist isn’t so sure.

In the C story, Phantom Limb pledges commitment to The Sovereign, then immediately goes back on his word. This cannot end well. The Sovereign is a spooky distorted head in a TV set; one would do well not to cross him.

Both Henchman 24 (or is it 21?) and Brock wish to commit to tattoos. Both attempts are abortive. In the henchman’s case, the abortion is voluntary. This foreshadows the abortion of Dr. Girlfriend’s attempts to get through her wedding to The Monarch. Both the tatoos and the wedding are commitment ceremonies.

A note on The Monarch’s and Dr. Girlfriend’s relationship: if it continues along the lines it is, it’s doomed. It cannot end happily. These two have issues, and I’m not talking about dressing up in costumes and living in a flying cocoon. Dr. Girlfriend wants a commitment, but she wants The Monarch to change who he is in order to get it. This is a common and tragic mistake. Dr. Girlfriend wants The Monarch to give up arching Dr. Venture, but that is all The Monarch knows. He only defines himself in opposition, he has no positive identity. If he’s not arching someone, what is he going to do with himself? Dress up in the costume, fly around in the cocoon and — what, exactly? What kind of a way is that to live? And once his identity is taken away, how will he maintain his appeal to Dr. Girlfriend? What is her attraction to him after all? He’s a whining, petulant, fussbudget. She must be attracted to him for the command and drive that he possesses when arching Dr. Venture. Take away his hatred and his plans for destroying Dr. Venture and what will come to the fore? Where will he direct his energy? Dr. Girlfriend (Dr. Wife? Dr. Life-Partner?) makes the classic mistake of gutting her relationship when she thinks she’s solidifying it, a rare manipulative misstep for this otherwise canny woman.

(Incidentally, this may answer a question from last week. Why wasn’t The Monarch present during the raid on the Venture Compound? He apparenly had a hot date with Dr. Girlfriend in their seedy motel room.)

Dr. Orpheus is disappointed with the Order of the Triad. Jefferson Twilight seems okay with going along with arching Torrid, but The Alchemist is wavering in his commitment to costumed arching (his comment about being “disguised as a paunchy gay man” is a telling moment). The team cannot even perform the Man-Mound without the two lesser team members griping about it (and no wonder — The Alchemist, being the shortest member, should be at the top of the mound, not Dr. Orpheus — what are they thinking?). Dr. Orpheus wants to have a “practice session” (another kind of commitment ceremony), which The Alchemist derails by bringing a treat that Jefferson is susceptible to (thereby demolishing Jefferson’s commitment to sobriety).

While The Monarch is commiting to Dr. Girlfriend by promising to marry her, the henchmen are proving their commitment to The Monarch by capturing Dr. Venture and his family. (Strangely, the henchmen, while ever loyal, are beginning to show signs of independent thought — they gripe about hench-life out in the open now without apparent fear of repercussions — could this represent a more democratic atmosphere around the cocoon?)

Later, Hank and Dean are each becoming seduced by the henchman lifestyle. Hank is attracted by its juvenile, play-acting dress-up side while Dean is interested in the technical aspects. In fact, Dean shows more interest in the flying cocoon than he’s shown in his father’s projects in two seasons. Thematically, these storylines don’t exactly fit: one does not, after all, commit to being a child or a sibling, one is simply born that way. One does, however, commit to being a “Venture Brother,” and if they can be attracted to the hench-life, can the end of the Venture-brand line of adventures be far behind? (At the moment Hank puts on the “evil Hank” beard, he is distracted by the henchman’s alarm clock, a Rusty Venture clock of all things, with Jonas’s voice calling for Rusty to “wake up.” Is Hank experiencing an awakening of a sort by donning his henchman garb and his “evil Hank” beard?)

In the middle of all this, Dr. Venture has a revelation: Dr. Girlfriend is Charlene, the woman who turned him into a caterpillar (I know that everyone reading this knows that, I just enjoy typing phrases like “the woman who turned him into a caterpilar”). And so he does something rather alarming; after an adulthood filled with grumpily harumphing at the whole costumed-arching lifestyle, and at The Monarch in particular, he goes ahead and does something that cannot help but actually make him a genuine enemy of The Monarch. So while The Monarch has hated Dr. Venture all this time for no reason at all, Dr. Venture, on the day The Monarch has vowed to stop arching him, has given him something to really arch about.

The special surprise guest at the wedding is, of course, David Bowie. Which prompts the question, what does David Bowie represent in the Venture Bros cosmos? If the theme of tonight’s episode is commitment, then Bowie, chameleon without peer, would seem to represent the pinnacle of non-commitment. Bowie’s career (and by “career” I mean from 1969 to 1980; I can’t account for the ensuing 26 years of fitfully entertaining product, which puts Bowie more into the “squandered potential” theme of the show) was founded on what we might call “success through transformation.” So then we ask, well, who in The Venture Bros has succeeded through transformation? We could say that The Monarch has succeeded through transformation, if you can call what he does successful. The butterfly is the ultimate symbol of transformation, the ugly creeping worm that becomes the beautiful floating flower. And now he is contemplating another transformation, from arch-villain to, what, house-husband?

Well, at least it’s a step: Rusty and Brock have both refused to transform at all, they have both remained stuck in their adolescent mindsets for over twenty years now, Rusty with his frustration and curdled dreams and Brock with his devotion to Led Zeppelin, which even the butterfly-dressed Monarch puts down as juvenile.

Or maybe the Bowie reference is not to transformation but to masks: many of the characters in Venture Land wear masks, but Dr. Girlfriend has gone through more then most. Is she, like Bowie, a chameleon, or does she just not know who she is? First she’s Lady Au Pair, then she’s Etheria, now she’s Dr. Girlfriend: who is she “really?” Is there a symbolic weight to chameleon David Bowie “giving her away” at the wedding (and quoting “Modern Love” before the ceremony)? Does this represent Dr. Girlfriend’s farewell to masks, to false identities? Will we (and perhaps she) now find out who she “really is?”

(I see that David Bowie’s henchmen, at least for the road, are Iggy Pop and Klaus Nomi. A formidable team — but where are Fripp and Eno? Are they more of a “brain trust,” perhaps, that Bowie keeps in a vat of viscous liquid hooked up to electrodes, or does Eno outrank Bowie at this point?)

(A commenter on urbaniak‘s blog suggests that David Bowie is, in fact, The Sovereign. There is evidence to suggest that this is so. The Sovereign, after all, lets slip to Phantom Limb that he “has a wedding” to get to, and we see no distorted, floating head at the wedding. Unless The Sovereign is Sgt. Hatred, or Miss Littlefeet, both of which seem doubtful.)

UPDATE: Another aspect of Bowie’s work occurs to me, his deep and abiding belief in space aliens. In “Space Oddity,” space seems to be quite empty and lonely, but from Ziggy Stardust through Young Americans’ “Somebody Up There Likes Me,” he turns to the idea of invaders from space as Earth’s only salvation. (It’s not an accident that Ziggy’s band is called the Spiders From Mars.) His interest seems to have peaked with The Man Who Fell to Earth, but the appearance of genuine alien Klaus Nomi as a bodyguard suggests an exciting new avenue exploration in the Venture universe.

Venture Bros: Viva los Muertos!

I don’t think it’s too much of an exaggeration to say that “Viva los Muertos!” is the reason that television was invented.

No joke: just the other day I was asking myself if there is an upper limit to the themes and issues that an episode of Venture Bros could address.

Question answered.

The themes this week are among the grandest imaginable: war, authoritarian control, the one-ness of existence, the border of life and death and the nature of humanity.

We start in the middle of a war film. The Monarch is sending his henchmen into battle. We are behind the orange-tinted goggles of one of them. The Monarch, unlike last episode, is not there for the invasion; no, this battle he’s sitting out, content for now to send his men to their deaths, as any good general does in any war.

It’s present day, but the language of the henchmen comes from older war films. The trench recalls World War I and the reference to “taking this hill” recalls Paths of Glory, Kubrick’s study of military cruelty, where primping generals sip tea in chateaus while sending their men to die for no reason at all. It makes me wonder what the Monarch’s goal for this incursion was, why he’s not participating today, what he has to do that’s more important.

As in Paths, the incursion is a failure and our POV henchman is quickly dispatched by Brock, only to be brought back to life by Dr. Venture, in the manner of Frankenstein’s Creature, just in time for that landmark film’s 75th anniversary. “The Holy Grail of super-science,” Rusty crows, life from death. Death, science wishes to show, is not the undiscovered country, the land from which no traveler returns, but just another tool for maximizing profit. The fact that Venturestein can hardly be called human atthis point seems to be beside the point — Dr. Venture has re-animated dead flesh and stands to profit greatly from it.

Like Frankenstein’s Creature, “Venturestein” identifies Dr. Venture as his father, a notion Dr. Venture quickly quashes. “I get enough of that noise from these two,” he says, gesturing to Hank and Dean. This brings up an important and vital aspect of Dr. Venture’s parental instincts: why does he keep bringing Hank and Dean back to life, since he has no interest in being a father? “Dean, as of right now Hank is better than you,” he snaps at his children, as good an example of bad parenting as we are likely to see on television this season. And yet we will see later in the episode that parenting isn’t always just a nurturing instinct born of love, it can also spring from a desire to mold and warp, to control and shape an unformed mind. Dr. Venture puts Venturestein in Hank’s bed to teach him, what else, the relative value of a life of legalized slavery (which explains his afro head and the beat about Hank and Dean trying to find “Africa-America” on the globe), or, as Venturestein succinctly puts it, “Prostitution!”

Now then: The Groovy Gang.

The average writer says “Hey, let’s have the Mystery Gang meet up with the Venture Bros. It’s a natural. And they can be middle-aged and failed, driving around in a beat-up van solving mysteries.” But it takes the genius of the creators of Venture Bros to take the mystery gang and invert them from optimistic, youthful children of the 60s (don’t forget, Fred, Daphne, Velma, Shaggy and Scooby were, literally, on their way to the Woodstock festival when they were waylaid by their first mystery) to a pack of the darkest, most repugnant criminals of ’68-’78, namely Ted Bundy, Patty Hearst, Valerie Solanas and David Berkowitz (and his talking dog Harvey). And so “Ted,” the leader, becomes a vicious, controlling thug, good looking and charming on the outside but murderous and brutal on the turn of a dime, threatening to put Patty “back in her box” and regularly threatening “Sonny’s” life. (It’s hard to see why Val, whose real-life counterpart felt that her life was controlled by men in general and Andy Warhol in particular, would be part of this gang, except that she seems to see herself as some sort of protector/predator of victimized Patty.)

Ted pulls the van up to the Venture compound in a thunderous rainstorm (a rare use of “atmosphere” in the Venture world). “I smell a mystery!” he says, apropos of nothing. Or is it? Ted can’t know about Venturestein running amok inside the compound. What mystery is he referring to? And then we realize: Ted Bundy, and all intelligent, cold-blooded killers, fascinate us precisely for their investigations into the same mystery that Dr. Venture is “prostituting” inside the compound: the border between life and death. In a sense, Ted is always pursuing not just “a mystery” but the mystery — what happens to us when we die?

The serial killer cannot keep himself from his quest in the same way that Dr. Venture can’t keep himself from his own. One kills from insanity and the other brings men back to life from a different kind of insanity. The killer answers to a higher power (a point driven home by Sonny’s dog, growling at him about “The master’s orders”) while the scientist pretends to be that higher power to reverse the process. And so unholy Creator and equally unholy Destroyer are set on a collision course on the Venture compound on a dark and stormy day.

(There’s more than a little of George W. Bush in Ted as well. When asked for reasons for invading the Venture Compound, Ted invokes both God and the lack of gasoline as reasons enough. When Sonny questions further, he’s met with accusations of disloyalty and the barrel of a gun.)

Because Venture Bros episodes consistently teem with twinning and reflections, our B-story this week concerns a more serious version of Creator and Destroyer. Brock feels bad about killing Venturestein (twice) and crashes Dr. Orpheus’s shaman party (or “Dracula factory!” as Ted puts it, completing the “Universal Monster Movie 75th Anniversary reference” beat [and also bringing up vampirism, the other most-potent “life from death” myth of the 20th century]) . The shamans all drink wine made from the ego-destroying “Death Vine” (which reminds Brock a little too much of “a Jonestown thing,” yet another reminder of authortarian control, a bad father, run amok) and when Brock tells his story of killing the henchman, the oldest, most respected shaman tells a seemingly unrelated story of having sex with a dolphin.

Or is it unrelated? Sex, after all, is the opposite of murder, and the dolphin could be seen a purer, more instinctual level of existence. The dolpin, which science has shown is the intellectual equal (if not superior) of humanity, manages to live a free, toil-free life in spite of its intelligence. It sees no need to organize into complex societies, print money, go to war or enslave children (to name only the most radical of the offenses listed this week). The shaman’s story of the dolphin, in spite of its absurdity, is truly the opposite of Brock’s story of senseless, state-sanctioned murder.

Dr. Venture is a bad father, and so is Ted, and so is the unseen government constantly lurking in the background of the Venture world. Dr. Venture has finally achieved success; the army wants 144 of his Venturesteins to use as walking bombs; Rusty has no trouble taking the order, and assumes that Brock, the born killer, will simply “make some dead bodies” for him.

But Brock is changing; he’s questioning the limits and certitude of his powers, his “license to kill.” And so he “drinks the Kool-Aid,” as it were, with the shamans (who lose their lunches, as well as their egos, as they drink from the Death Vine) and has his hallucination involving that same dolphin spoken of earlier. The dolphin explains the importance of empathy and the oneness of existence to Brock (just as its darker twin, Groovy, commands Sonny to murder on the behalf of the mysterious “Master”). The hallucinatory dolphin is then, of course, murdered by a hallucinatory Hunter Gatherer, Brock’s own authority (and father-) figure. Hunter sets Brock straight on his nature and purpose in the world. We are here to kill, he insists, on the behalf of our masters, invoking another Kubrick war film, Full Metal Jacket. It’s enough to snap Brock out of his confusion and set him back on his path of righteous destruction.

Meanwhile, in another part of the compound, Sonny sees Hank and Dean and freaks out. They’re supposed to be dead. He knows because he killed them some time earlier. And again, it’s funny but it’s also not. The serial killer, the one who sees it as his brief to send souls off to the undiscoverd country, confronted with two of those souls returning? The Destroyer confronted with two souls undestroyed? It’s as serious and confounding idea as the scientist bringing the dead back to life.

And so there’s a showdown in the cloning lab, where Hank and Dean are confronted with their own confounding image, rows and rows of themselves (providing the show with its best line, “I think they’re in a ‘saw their own clones’ coma”). Ted and Sonny are ready to kill Hank and Dean, but we see that, as murderous as they are, they are, after all, mere amateurs. Brock is a highly trained, skilled professional, acting on behalf of a government (and the family he loves).

Dr. Venture comes in just in time to snap Hank and Dean out of their stupor, pulling, what else, a great, paternal lie out of his back pocket, a parental fib, prompting Hank and Dean to exclaim that Rusty is “the best dad ever!” bringing the episode full circle. The ultimate bad father has, magically, become the ultimate good father, at least in the eyes of his cruelly manipulated children, and that’s a lesson that needs to be learned, especially with an election five weeks away.

UPDATE: ![]() mcbrennan, typically, has spurred a few more thoughts, mainly about Dr. Venture and his back-up plan to, essentially, send his own children off to die as brainless zombies in an unnamed war. I was reminded of two Leonard Cohen songs. He was writing, of course, about Vietnam, but they will serve here:

mcbrennan, typically, has spurred a few more thoughts, mainly about Dr. Venture and his back-up plan to, essentially, send his own children off to die as brainless zombies in an unnamed war. I was reminded of two Leonard Cohen songs. He was writing, of course, about Vietnam, but they will serve here:

“Story of Isaac” contains this verse:

You who build these altars now

to sacrifice these children,

you must not do it anymore.

A scheme is not a vision

and you never have been tempted

by a demon or a god.

And “The Butcher” begins:

I came upon a butcher,

he was slaughtering a lamb,

I accused him there

with his tortured lamb.

He said, “Listen to me, child,

I am what I am and you, you are my only son.”

Venture Bros: I Know Why the Caged Bird Kills

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Shakespeare wrote “the course of true love never did run smooth,” and while this episode of The Venture Bros shares much with that play, including star-crossed lovers and magical spirits, I doubt Shakespeare could have ever come up with a path to true love involving Catherine the Great, Henry Kissinger, a haunted car and a refugee from American Gladiators.

As with any love story, “I Know Why the Caged Bird Kills” has two protagonists, The Monarch and Dr. Venture. Both protagonists have love problems (to say the least), but for the moment, neither protagonist can pay attention to them. (Typically for this show, the Monarch’s plot is active, with him trying to solve his administrative problems, while Dr. Venture’s plot is passive, with him merely trying to get rid of his immediate problem so that he can go back to his life of steadily increasing failure.)

The Monarch’s attention is taken up by an immediate problem, that his plans to attack Dr. Venture are failing. His henchmen (at least 21 and 24) believe that the problem is one of armament (which is absurd, as the attack shown at the top of the episode is the most well-armed and effective in The Monarch’s history). Meanwhile, Dr. Venture is being harrassed by a vengeful Oni.

Meanwhile, The Monarch is visited by a mysterious stranger, Dr. Henry Killinger and his magic murder bag. The Monarch, impressed with Killinger’s organizational skills, allows him free access to his staff and secrets. In no time at all, Killinger has an elite staff of Blackguards in cool suits and has completely re-organized the Monarchs’ operation (Literally, in no time at all. Killinger does all this in the time it takes for Drs. Venture and Orpheus to walk from the library to the parking lot).

Henchman 24, suspicious of Killinger’s intentions, refers to him as a “sheep in wolf’s clothing,” and while that sounds like a mere malapropism, it’s actually a key line in the episode. Because we see that, in each plot here, love comes disguised as hate, tenderness disguised as threat. Myra shows her love for Hank and Dean by kidnapping them, 21 shows his love for the Monarch by bringing in Dr. Girlfriend to infiltrate and assault the cocoon (and ends up falling in love with her, but that’s another story). I will also argue that the Monarch’s obsession with and attempts to destroy Dr. Venture also constitute a kind of love, one paralleled by Myra’s obsession with and attempts to destroy Dr. Venture’s family. (It also occurs to me that Henry Kissinger was the inspiration for Dr., ahem, Strangelove.)

And then of course there is Dr. Killinger, who turns out to be not a malevolent figure of doom but a magical spirit of love and reconciliation (would that his real-life counterpart turn out similarly), and the Oni turns out to be working for him. Killinger is shown to be a fat, male version of Mary Poppins, which, again, seems completely lunatic on the face of it, but underneath has a deep thematic resonance with the rest of the show.

The protagonist of Mary Poppins, lest we forget, is not Mary Poppins but rather the father. What does the father in Mary Poppins want? The same thing as Dr. Venture — to have someone, anyone besides himself take responsibility for raising his children. A key difference between Dr. Venture and Dr. Benton Quest is that Race Bannon is assigned to be a bodyguard for Dr. Quest’s son Jonny, Dr. Venture has hired Brock to be a bodyguard for himself; the boys’ safety is never anywhere on Dr. Venture’s list of priorities. Brock, the much better parent of the two, seems to take on the boys’ safety himself, but only to the extent that it’s usually too much trouble to clone them again. If the boys die, well, there’s always more where that came from. The father of Mary Poppins at least hires a nanny; Dr. Venture is content to leave that job to an inadequate robot and the “lie machines” that talk to them in their sleep. The father in Mary Poppins, of course, learns his lesson and re-centers his life around his children; Dr. Venture, I fear, will never learn that lesson.

The theme of this episode is the course of true love, but there is a sub-theme of misguided rescue. Hank and Dean, out practicing their driving skills, happen upon a stricken woman, who turns out to be a deranged ex-girlfriend of Dr. Venture. They set about rescuing her, but end up being taken captive by her. Later we will find that she feels that she is “rescuing” them from Dr. Venture. The henchmen misguidedly try to rescue the Monarch, and even take turns rescuing each other at different points of the episode.

Of the episode’s short-circuited love affairs, the most elliptical is the one between Drs. Venture and Orpheus, which seemingly ends with Dr. Venture hysterically accusing Dr. Orpheus of coming on to him, then mysteriously seems to begin again when he, minutes later, casually suggests that they watch pornography together. This rocky, contentious relationship is presented as a contrast to the other “true loves” of the episode.

In an episode rife with parallel scenes, Brock and Helper are given a nice pair where, in one scene, Brock attempts to educate Helper on the subject of Led Zeppelin, and in the next, Helper is educating Brock on the poetry of Maya Angelou.

The advice Dr. Orpheus gets from Catherine the Great’s horse is never revealed — but given the circumstances, that might be for the best.

(Strangely enough, although Myra’s story is explained away by Brock, her own version of events makes more sense. In her version, she rescues Dr. Venture’s life during the unveiling of the new Venture Industries car, and later the two of them have sex in that same car, and it is that car that the Oni chooses to haunt in order to bring Dr. Venture to Myra. So perhaps Brock’s story is the inaccurate one after all.)

Venture Bros: Guess Who’s Coming to State Dinner?

“Guess Who’s Coming to State Dinner,” like The Big Lebowski, is about people living in a world where things once meant something but don’t any more. That’s a major theme for Rusty Venture in any given episode of course, but it’s stated pretty boldly across the board here. Just as the burnouts and washups of Lebowski try in vain to scare up some of the glamour and intrigue of the 40s Los Angeles of The Big Sleep, the heroes of “Dinner” all live in the shadow of some greater, more genuine heroism.

Bud Manstrong, who’s been in space for years with a (supposedly) irresistable woman (whose face we never see), feels that his mission and his lack of sexual experience somehow combine to make him a hero. He lives in the shadow of the genuine heroism of the Space Age astronauts and is cursed with a name that recalls both Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong. He has a domineering mother with the hair and pearls of Barbara Bush (but the mouth and drinking habits of Martha Mitchell). His haircut, his “manly man” physique and attitudes, his imagined virtue and rectitude, his humiliation at the hands of Brock, have all collided to make him into quite a quivering sexual ruin.

Rusty complains from the start that Bud is no hero (and who are the “terrorists” responsible for crashing the space station? Could it be that the Guild has actually committed a crime, caused — gasp — an actual death?), and he’s correct, but also wrong at the same time, as he believes the title of “hero” belongs to himself for owning the space station. Of course, he owns it only by default, since he inherited it from his father, just as we have inherited the space program from a previous generation, and have turned it from a stunning, still-incredible symbol of adventure and the American Spirit into a depressing series of milk-runs for the Pentagon.

Vietnam, itself a ruinous war for men who sought to become heroes, is mentioned in passing. Vietnam, of course, has acquired its own heroic myth, that of the brave soldier who has made it through hell. Brock mentions it to Rusty, who, of course, brings up that Brock was too young to have fought in the war. Brock says that he never mentioned fighting in the war, thus reducing Vietnam’s shadow of World War II heroism to a sadder, even more pale charade.

“Phonies!” says Bud’s mother, dismissing all the guests at the table while slipping a hand onto Brock’s thigh. Brock, as usual,is the simplest, least complicated, most comfortable man at the table. Brock is a hero every week, a “real man,” but doesn’t brag or make a big deal of it. Indeed, he often tries to reason with the man he’s about to kill or dismember, stating flatly what’s about to happen and how the other man can avoid a grisly fate. A real hero knows that heroism is often something to be avoided and that discretion is the better part of valor.

But yes, the President is a phony and the head of the Secret Service is a phony (with his masking-tape perimeter and his priceless halting line-reading regarding same). The old cleaning woman seems genuine, and of course “saves the day” in the end, proving that heroism can often be found in simple wisdom and household common sense.

“Dinner” borrows the plot of The Manchurian Candidate, and just bringing it up shows how far we have fallen from the Space Age. The original was, and still is, a subversive, mind-blowing, utterly original movie. Its remake, while not without merit, can’t hope to hold a candle to the brilliant, unnerving Cold War masterpiece.

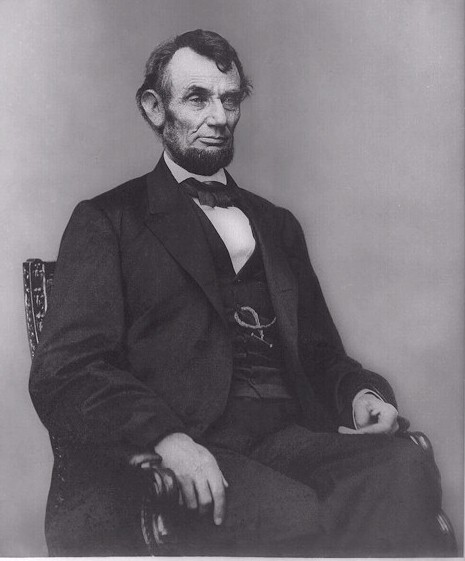

Who else is a true hero in this episode? Well, Dean as usual tries, although he’s beset with Hank’s taunting and his own almost total lack of education. It’s one thing for a pair of teenage boys to be unfamiliar with The Manchurian Candidate, but to be unfamiliar with the career of Abraham Lincoln is something else.

Lincoln, one of the greatest presidents who ever lived (another, Roosevelt, gets Lincoln’s approval), also steps forward as a true hero, although he is saddled with the dimwitted boys, allegations of homosexuality and his own limited ghostly powers. Even in the face of crisis and failure (he, after all, saves the wrong man and for the wrong reason and is shot in the head for the second time in his existence), he retains his good humor, elegance and panache. Maybe it’s impossible to be a true hero in these times, but it’s at least possible to attain grace and keep your sense of perspective.

(Lincoln’s plan for saving the president, by the way, represents the most imaginative and yet prosaic method of “throwing money at the problem” I’ve ever seen dramatized.)

As Manstrong is unmasked as an unheroic, twitching masturbator he exclaims “My God, it’s full of stars!” Which is, of course is a reference to 2001: A Space Oddessey, the ultimate Space Age cultural triumph, and another shameful reminder of how far our culture has fallen.

The chip in the back of Manstrong’s head turns out to be a massive red herring. Given the episode’s theme it could hardly be otherwise. The question remains, however, why? Why is the chip in the back of his head? Did he put it there? Did the doctors? Or was it part of the accident, too close to the nerve to remove, just another random occurence in a rudderless world?

Venture Bros: Fallen Arches

Often I will watch an episode of Venture Bros more than once to catch the asides and subtexts; this is the first time I had to watch it twice just to sort out all the plot strands.

In your typical well-written 22-minute TV episode, there will be an “A” story and a “B” story, ie: Homer quits his job while Lisa works on a science project. Often the two stories will link up towards the end of the episode, but not always.

In “Fallen Arches” I found an “A” story, a “B” story (with its own sub-plot), a “C” story, a “D” story, an “E” story and, incredibly, an “F” story.

The “A” story is: Dr. Orpheus has, for some reason, vaulted from the backwaters of “down-on-his-luck necromancer with no job renting Rusty’s garage” to “leader of superhero team with his own private island.” Apparently he, like Rusty, was once quite the thing, but, like many men, found himself burdened and diminished by marriage, fatherhood and responsibility. Wife gone (why is unclear, although at this point of the show literally anything is possible) and daughter of age, he suddenly “qualifies” for an arch-villain, to be supplied by the Guild of Calamitous Intent. (Why the Guild exists, how it operates, and why Dr. Orpheus suddenly qualifies is unclear, but I’m sure time will tell.) He gathers up the members of his old team, The Order of the Triad, and auditions arch-villains.

The “B” story, I would say, is Rusty and his Walking Eye (glimpsed in the season 1 titles, it now has its own plot-line). He’s built a useless machine and is bitterly frustrated when no one recognizes its brilliance. Rusty also takes time out (because the episode is, apparently, not plot-heavy enough) to chat with Dean about the birds and the bees, a chat that leaves neither one any more enlightened than before.

The “C” story involves the Monarch’s Henchmen and their attempts to, on what apparently is a slow day in Monarch-land, branch out into supervillainy themselves. Comedy ensues.

The “D” story involves a homely prostitute and her sad misadventure at the hands of The Monarch, who, after receiving his pleasure (whatever that is), turns into some kind of Thomas Harris villain on her and forces her to undergo a series of life-threatening tests in order to leave his cocoon. An Edgar Allan Poe quote is thrown in for good measure.

The “E” story involves Hank and Dean solving the Mystery of the Bad Smell in the Bathroom (and the disappearance of Triana).

The “F” story involves Torrid, who looks like a cross between Deadman and Ghost Rider, his misadventure in the bathroom and his attempts to impress Dr. Orpheus and Co., bringing the plot full-circle.

The title is “Fallen Arches” but it could have just as accurately been “False Impressions,” as each character in the episode is trying to impress someone, and often failing. Rusty wants to impress his family with the Walking Eye but fails, so instead tries to impress the Guild creeps auditioning for Dr. Orpheus instead. This works to some degree, but not without Rusty debasing himself with his Whitesnake-music-video/Tawny Kitaen “washing the car” vamp. And finally Rusty must face the fact that he has impressed no one in his house, that his inventions, his career and his life is a failure, even while Dr. Orpheus is in re-ascendency. The auditioners are desperately trying to impress Dr. Orpheus and company, and mostly desperately failing. The Henchmen want to impress some ideal, invisible female and get nowhere near even failing. The Monarch wants to impress the prostitute and does, in a way, but probably not in the way he’d like to. Dean wants to impress Triana but fails to even get her attention, although he does succeed in impressing Hank, later in the show, with his ability to actually solve a mystery. Finally, Torrid succeeds in impressing Dr. Orpheus by kidnapping his daughter, although how exactly he accomplished that, and how she ended up on Dr. Orpheus’s private island, is left unclear. I’m unfamiliar with Lady Windermere’s Fan but I’m willing to bet its plot revolves around someone trying to impress someone else too.

Who is not trying to impress anyone in this episode? Well, Brock is perfectly comfortable in his skin and doesn’t care about impressing Dean with his abilities to deliver Wilde. He’s just as happy to kill Guild villains in a tux as he was to kill them while naked a few weeks ago. The prostitute doesn’t seem too concerned about impressing the Monarch although she gives it the college try. Dr. Orpheus’s team seems quite self-effacing and comfortable with themselves, and Dr. Orpheus, with his newfound status as superhero, himself seems more confident and relaxed in this episode than ever before. Triana, of course, is a goth chick and so is genetically incapable of trying to impress anyone. Sadly, Dr. Girlfriend is briefly reduced to trying to impress Dr. Orpheus as the hastily-considered Lady Au Pair. It doesn’t take much for her to regain her self-esteem however, Jefferson Twilight’s mention of her deep voice is all it takes.

Any one of these plot lines would have been enough for most shows. This episode had the breathless pace of the Christmas special but was twice as long. It makes me wonder, aloud, what a Venture Bros feature might be like. Could this kind of pace be sustained over 90 minutes? Would there be 18 different plot lines? Would it be like It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, but funny, and short?

The Guild exists, apparently, because all superheroes require an arch-villain. Otherwise how would we know they’re heroes? It wouldn’t surprise me to learn that the Guild is financed by superheroes themselves. My son Sam understands the concept and he can’t even read; he knows that Dr. Octopus fights Spider-Man, Mirror Master fights The Flash and Sinestro fights Green Lantern. When he sees a character he doesn’t know, before he asks “What does he do?” he’ll ask “Who does he fight?”

Reagan understood that every superhero needs an arch-villain, and so does George W. Bush, although Bush made the poor decision to go for the “better Bad-Guy Plot” instead of going after the real villain. The American people have begun to understand that if you’re Superman, you fight Lex Luthor, not the Mad Hatter.

Venture Bros: a closer look

![]() mcbrennan posted this lengthy, well-considered analysis of The Venture Bros in response to my entry on last week’s “Victor-Echo-November” episode. I thought it was worth bumping up to a new entry. She starts with quoting a paragraph of mine, then heads straight into the core of the show, which becomes more interesting the more you examine it.

mcbrennan posted this lengthy, well-considered analysis of The Venture Bros in response to my entry on last week’s “Victor-Echo-November” episode. I thought it was worth bumping up to a new entry. She starts with quoting a paragraph of mine, then heads straight into the core of the show, which becomes more interesting the more you examine it.

Take it away, Cait:

“In a way the whole show is about arrested adolescence, with each character presenting their own take on the concept, and that includes Mr. Brisby. Hank and Dean are the most clinical and literal of Team Venture, being seemingly unable to make it out of adolescence alive. Dr. Venture’s more mature self literally made its break from his body to go live on Spider-Skull Island (or is Jonas his less mature self, living his playboy lifestyle?). Phantom Limb may be a sophisticate, dealing in bureaucracy and insurance and masterpieces of Western art, but in a way there’s more than a touch of Felix Unger in him, a fuss-budget who uses his sophistication to hold the world at arm’s length so that he doesn’t have to deal with the messier aspects of adult life, like maintaining a stable relationship or taking responsibility for his actions.”

There’s so much truth to this. I’m not sure if it’s arrested adolescence or just pervasive failure–failure to live up to impossible standards or to fulfil early promise, especially. Whether it’s Rusty’s boy-adventurer pedigree, Billy’s boy-genius, Brock’s football career, or the Monarch’s blueblooded trust fund origins, so many of these characters were destined for greatness and got stuck. Another specific theme I connect with is how the…the knowledge and expertise and talents of all these characters are essentially useless outside their insular little world of adventuring and “cosplay” (or costume business, in deference to the Monarch); the 60s/70s backgrounds and social “rules” are no accident. The world they learned how to live in has passed them by; The idealism of the original Team Venture is as obsolete as Rusty’s speed suits. Brock’s cold war is over; even his mentor has left it all behind, including his gender. The Guild is in league with the police. Faced with the prospect of trying to make normal human connections and fit in with the contemporary world we know (if such a thing even exists for them), Dr. Venture, the Monarch and company instead spend their time riding the carcasses of the dead past, reenacting costume dramas to keep them from going insane with boredom or despair. The scale of their “adventures” is telling: There are no world-changing inventions and no world-domination schemes. And for all the Marvel-inspired costumed supervillains, there arealmost no heroes left, certainly none in costume (outside of that ethically dubious blowhard Richard Impossible, whose entire empire sits on the rubble of Ventures past). I think that’s one of the reasons that Brock in particular can be so emotionally engaging–he’s the heart of the show, trying to hold the universe together as it spins off its axis, protecting the family he loves and trying to safeguard the next generation so that someday, things will be different. He lives by a code of honor, something maybe only the Guild still recognizes. Orpheus plays much the same role for Triana, though she and Kim are more a product of our world, and more able to see the Venture family and their nemesis as anachronisms. Triana feels for the boys, but she won’t end up like them. We hope.

Interesting also that in this world where family is so key, all the mothers are missing (Hank and Dean’s? Rusty and Jonas Jr’s? Triana’s? The Monarch’s? Just for starters…) Interesting also that the strongest female character on the show may or may not have arrived at womanhood through unconventional means, and we certainly know that the man who was like a father to Brock is now more of a mother-figure (of course, the transgender thing may be just a red herring where Dr. Girlfriend is concerned, but leave me my illusions.)

As a more or less failed child prodigy myself, I feel for these characters even as I fear I’m probably going to share their fate. I suppose sitting up at 3am writing a 5000 word essay on a cartoon is not going to change that. 🙂 But the Venture Bros. is of course much more than a cartoon, and I’m not kidding when I say it’s the best show on television. It’s a privilege to live in a time where you get to experience firsthand something that is both great art and great fun in pop culture. There’s so much going on here, so much to think about, that it’s just a delight to watch every week.

Venture Bros: Love Bheits

Random thoughts while tripping through the fragrant copse of tonight’s episode:

*The guy at the beginning of the show, standing on the volcanic landscape, turns to the camera and, for the aide of the illiterate, announces “Underland,” with a gesture as though he were ushering us into a swank restaurant. More establishing shots should be like this. I’d love to see a shot of Central Park, with the Empire State Building in the background, and a title that says “New York City,” and THEN have a guy, a cab driver or homeless guy, come on screen and say “New York City,” with the same kind of maitre-d gesture.

* Just yesterday I was thinking to myself, “I wonder where you would go to get a Slave Leia costume?” (The answer, for those interested, is here.)

*Oh hey, Luke and Leia are twins, just like Hank and Dean! And I have a feeling that Hank and Dean may not have yet met their “real father” yet either.

*So, wait. I don’t get it. You can say “Chewbacca” in an episode, but you can’t say “Batman?”

*Little miniature timberwolves. Are they bred that way, or do they naturally come in that size in Underland, perhaps because of the lack of food available? Or are they, shudder, timberwolf puppies?

*I was delighted to see Catclops, Manic 8-Ball and Girl Hitler again. I wish we had seen that Manic 8-Ball got a position in the new government at the end. Don’t tell me he died in confinement! The “tiger bomb” couldn’t kill him!

*The “cat hair in the glass of drinking water” beat took two viewings to land for me. The first time I just went “Huh?” when the Baron drinks the water and gets a weird look on his face. And sometimes the dialogue goes by so fast it takes me two or even three viewings just to catch all the lines.

*Brock’s tender mentoring of Hank makes me think, again, that Brock and Hank have a relationship that perhaps even Dr. Venture doesn’t know about.

REFERENCES I CAUGHT:

Return of the Jedi (obviously), my favorite shot being the one where Girl Hitler adjusts her mask so that her moustache can see, an exact parallel to where Lando does the same thing.

Die Another Day for the shots of the X2 being forced down by super-magnet, with pieces breaking off and flying away.

Empire Strikes Back with the thing Underbheit lives in, and the shot of the toupee being lowered down on a thoroughly unnecessary apparatus to attach itself to his head.

Fantastic Four and Underbheit’s taste in the hooded robes of dictators of fictional Eastern Bloc nations.

Simpsons Comic Book Guy for “Lamest. Villain. Ever.”

Dr. Stranglove for ![]() urbaniak‘s “German Guy” accent on the henchman who can stop tonguing the slit (boy does that sound dirtier than it is).

urbaniak‘s “German Guy” accent on the henchman who can stop tonguing the slit (boy does that sound dirtier than it is).

Sin City for the row of women’s heads mounted to the wall.

Silence of the Lambs for the shot of the fingernails imbedded in the chair arm.

All this, and a sly comment on gay marriage too. Bravo!

Found this.

Venture Bros: Victor. Echo. November.

Here’s my own attempt to fix Triana’s face. ![]() Automatoid gave it a good try but stopped at her eyeball. It is also her brow that needs to be fixed. He is anal but I am analler.

Automatoid gave it a good try but stopped at her eyeball. It is also her brow that needs to be fixed. He is anal but I am analler.

Now, if he will be so kind as to instruct me as to how to put a jpeg into a comment…

Meanwhile, there is a stunning new episode of The Venture Bros. to discuss.

My local cable company lists the programming information of “Victor. Echo. November.” as “Dr. Girlfriend and The Phantom Limb go on a double date with The Monarch and a girl he met on the internet. New.”

Understatement of the year. Outside of the context of actually seeing the show, that reads like the word salad of a man with advanced Alzheimer’s.

Poor Triana. She loses everybody she cares about to this insanity. She’s the only pure character on the show, the only one who refuses to live in a state of arrested adolescence. Or hasn’t figured out that life is more fun that way. Which makes it especially ironic that she gets dating advice from Dr. Orpheus.

And then her face melts.

This episode does the best job yet of mixing together the mundane and exotic, with a plot simultaneously so complex and static that when Brock showed up in Dr. Venture’s lounge, naked, covered in blood and holding a severed head, it took me a moment to figure out what was going on.

The voice work on the show continues to astonish, predictably along thematic lines, taking the exoticism of the characters and welding it to the mundanity of their emotional lives. Mr. Urbaniak’s takes on Dr. Venture as the superscientist who is also a clueless emotional dork and Phantom Limb as a brilliant sophisticate who dresses in a purple leotard, both voices playing against the absurdity of the situation to arrive at rich characters in their own rights. Mr. McCulloch as The Monarch becomes more and more subtle as the layers of his personality get stripped away. In this episode he almost trades places with Dr. Girlfriend in terms of self-awareness, realizing how idiotic he looks while at the same time unable to give up his dream of supervillainy. We’ve come so far from the image of the Monarch masturbating while watching Dr. Girlfriend pretend to woo Dr. Venture. But it’s Patrick Warburton as Brock that really makes my jaw drop week after week, adding impressive depth and nuance to what could have easily been a standard Warburton beefcake part. I’ve always enjoyed his work (I’m one of the few adults who enjoyed The Emperor’s New Groove) but the way he consistently plays past the character’s brutality to hit at something more human and, well, caring, continues to touch me in ways I’ve never been touched before by a heartless assassin. And Ms. Nina Hellman as the new teenage supervillain is a beguiling, subtle creation light-years ahead from the cameos she’s delivered heretofore.

Indeed, it’s her character who casts a certain light not just on the absurd world of The Venture Bros but on our own as well. She’s already living in a state of arrested adolescence (the character, not Ms. Hellman), it’s just one beginning now instead of in 1965 so it looks relatively normal to us. Our own world routinely offers teenagers the chance to remain teenagers for the rest of their lives; The Monarch and his Henchmen are only the most extreme examples of it. The reason Dr. Girlfriend continues to beguile is that she is smart enough to do without all this supervillain nonsense, but another part of her continues to put on the outfits and date the costume-clad losers because, well, probably because it makes her feel sexy.

In a way the whole show is about arrested adolescence, with each character presenting their own take on the concept, and that includes Mr. Brisby. Hank and Dean are the most clinical and literal of Team Venture, being seemingly unable to make it out of adolescence alive. Dr. Venture’s more mature self literally made its break from his body to go live on Spider-Skull Island (or is Jonas his less mature self, living his playboy lifestyle?). Phantom Limb may be a sophisticate, dealing in bureaucracy and insurance and masterpieces of Western art, but in a way there’s more than a touch of Felix Unger in him, a fuss-budget who uses his sophistication to hold the world at arm’s length so that he doesn’t have to deal with the messier aspects of adult life, like maintaining a stable relationship or taking responsibility for his actions.

Speaking of which, of the stories offered this episode for the Phantom Limb’s origin, I hope Hank’s is the real one.

It’s this quality that makes Venture Bros stand out among the typically moronic Adult Swim block, critiquing the very quality the block tries to promote.

A couple of weeks ago I was discussing Adult Swim with a middle-aged friend of mine, and we got on the subject of Aqua Teen Hunger Force. I mentioned that I had tried to watch it recently and couldn’t get through a whole episode. My friend shrugged and said “Well, my developmentally disabled teenage sons like it.” And I laughed and then remembered that my friend actually has two developmentally disabled sons.

Speaking of arrested adolescence, I couldn’t help giving Triana’s face another try. This time I shifted all of her features to the right, making it more of a three-quarter profile. I’m learning Photoshop!

And, unable to leave well-enough alone, making her a little more anatomically correct and giving her a cheekbone. I’ll be a 10-year-old Korean boy yet!

The Venture Bros: Escape to the House of Mummies, Part II

The boys continue to warp and shatter the structures and expectations of form. It was funny enough that they put a fake “previously on The Venture Bros.” at the top of the show, but then they put a fake “next week on The Venture Bros.” at the end. So we’re apparently watching the second act of a three-part episode, what would in normal circumstances be released on DVD as The Venture Bros. Movie.

What makes this monkeying with structure great, of course, is the way it frees up the writers’ creativity. Why bother explaining how the boys got into the room with the spikes, or how Dean’s head got removed, or how Edgar Allen Poe got roped into this mess — that was all explained in Part I. And how will they get away from the bad guys, what will happen to the second Brock, how will Dean’s head get put back, all that will be explained in Part III. Right now, we’ve got the tumultuous, everything-in-motion Part II.

Of course, all that motion and calamity is the “B-story” this week. In the foreground is Rusty’s childish contest with Dr. Orpheus. The science/religion conflict that sparked in Episode 1 explodes into flames here, continuing Season 2’s theme of taking background ideas from Season 1 and making them the foreground here. Rusty abandons his family and tortures his friends, Dr. Orpheus fools his daughter and puts her into a coma, all for the sake of this contest. The goal of the contest? “Who can be the smallest,” of course, again, making the metaphoric literal. And when they both lose, they only do so because they both win! They’re both the smallest men!

And while it’s true that Orpheus is a know-it-all, I too felt the urge to correct the deity when he made the mistake of confusing Argos and Cerberus.

I once wrote for a comedy show, and the sketches for the show were developed as though the show were taking place in the late nineteenth century and were being written for the vaudeville stage. The producers insisted that each sketch must have a premise, development of the premise, a satisfying conclusion to the premise (called “the payoff”) and then a final “switcheroo” that they called “The Button.” This strict adherence to 100-year-old comedy rules helped ensure that every idea the writers had would eventually be turned from something everyone thought was funny to something no one thought was funny. After a few weeks of observing just how deadening this process was, I raised my hand in a meeting and said “I’m sorry, didn’t Monty Python prove, twenty-fiveyears ago, that you don’t need any of this crap? Why can’t we just think of funny ideas, keep them going for as long as they’re funny, then cut away when they’re not funny any more? Won’t that make the show fresher, more unpredictable, cut out all this dead time, and keep all the sketches from feeling exactly alike?”

It was questions like this that have kept me from working in television comedy for the past ten years.

So it’s good to see The Venture Bros., in its second season, being so voracious in its appetite to expand the boundaries of the possible in television.