Venture Bros: Guess Who’s Coming to State Dinner?

“Guess Who’s Coming to State Dinner,” like The Big Lebowski, is about people living in a world where things once meant something but don’t any more. That’s a major theme for Rusty Venture in any given episode of course, but it’s stated pretty boldly across the board here. Just as the burnouts and washups of Lebowski try in vain to scare up some of the glamour and intrigue of the 40s Los Angeles of The Big Sleep, the heroes of “Dinner” all live in the shadow of some greater, more genuine heroism.

Bud Manstrong, who’s been in space for years with a (supposedly) irresistable woman (whose face we never see), feels that his mission and his lack of sexual experience somehow combine to make him a hero. He lives in the shadow of the genuine heroism of the Space Age astronauts and is cursed with a name that recalls both Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong. He has a domineering mother with the hair and pearls of Barbara Bush (but the mouth and drinking habits of Martha Mitchell). His haircut, his “manly man” physique and attitudes, his imagined virtue and rectitude, his humiliation at the hands of Brock, have all collided to make him into quite a quivering sexual ruin.

Rusty complains from the start that Bud is no hero (and who are the “terrorists” responsible for crashing the space station? Could it be that the Guild has actually committed a crime, caused — gasp — an actual death?), and he’s correct, but also wrong at the same time, as he believes the title of “hero” belongs to himself for owning the space station. Of course, he owns it only by default, since he inherited it from his father, just as we have inherited the space program from a previous generation, and have turned it from a stunning, still-incredible symbol of adventure and the American Spirit into a depressing series of milk-runs for the Pentagon.

Vietnam, itself a ruinous war for men who sought to become heroes, is mentioned in passing. Vietnam, of course, has acquired its own heroic myth, that of the brave soldier who has made it through hell. Brock mentions it to Rusty, who, of course, brings up that Brock was too young to have fought in the war. Brock says that he never mentioned fighting in the war, thus reducing Vietnam’s shadow of World War II heroism to a sadder, even more pale charade.

“Phonies!” says Bud’s mother, dismissing all the guests at the table while slipping a hand onto Brock’s thigh. Brock, as usual,is the simplest, least complicated, most comfortable man at the table. Brock is a hero every week, a “real man,” but doesn’t brag or make a big deal of it. Indeed, he often tries to reason with the man he’s about to kill or dismember, stating flatly what’s about to happen and how the other man can avoid a grisly fate. A real hero knows that heroism is often something to be avoided and that discretion is the better part of valor.

But yes, the President is a phony and the head of the Secret Service is a phony (with his masking-tape perimeter and his priceless halting line-reading regarding same). The old cleaning woman seems genuine, and of course “saves the day” in the end, proving that heroism can often be found in simple wisdom and household common sense.

“Dinner” borrows the plot of The Manchurian Candidate, and just bringing it up shows how far we have fallen from the Space Age. The original was, and still is, a subversive, mind-blowing, utterly original movie. Its remake, while not without merit, can’t hope to hold a candle to the brilliant, unnerving Cold War masterpiece.

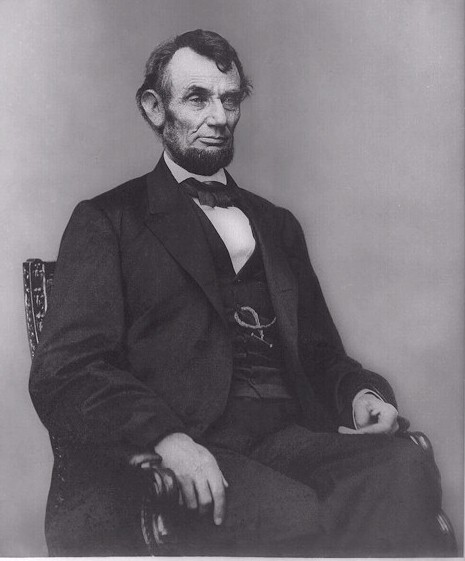

Who else is a true hero in this episode? Well, Dean as usual tries, although he’s beset with Hank’s taunting and his own almost total lack of education. It’s one thing for a pair of teenage boys to be unfamiliar with The Manchurian Candidate, but to be unfamiliar with the career of Abraham Lincoln is something else.

Lincoln, one of the greatest presidents who ever lived (another, Roosevelt, gets Lincoln’s approval), also steps forward as a true hero, although he is saddled with the dimwitted boys, allegations of homosexuality and his own limited ghostly powers. Even in the face of crisis and failure (he, after all, saves the wrong man and for the wrong reason and is shot in the head for the second time in his existence), he retains his good humor, elegance and panache. Maybe it’s impossible to be a true hero in these times, but it’s at least possible to attain grace and keep your sense of perspective.

(Lincoln’s plan for saving the president, by the way, represents the most imaginative and yet prosaic method of “throwing money at the problem” I’ve ever seen dramatized.)

As Manstrong is unmasked as an unheroic, twitching masturbator he exclaims “My God, it’s full of stars!” Which is, of course is a reference to 2001: A Space Oddessey, the ultimate Space Age cultural triumph, and another shameful reminder of how far our culture has fallen.

The chip in the back of Manstrong’s head turns out to be a massive red herring. Given the episode’s theme it could hardly be otherwise. The question remains, however, why? Why is the chip in the back of his head? Did he put it there? Did the doctors? Or was it part of the accident, too close to the nerve to remove, just another random occurence in a rudderless world?

Venture Bros: Fallen Arches

Often I will watch an episode of Venture Bros more than once to catch the asides and subtexts; this is the first time I had to watch it twice just to sort out all the plot strands.

In your typical well-written 22-minute TV episode, there will be an “A” story and a “B” story, ie: Homer quits his job while Lisa works on a science project. Often the two stories will link up towards the end of the episode, but not always.

In “Fallen Arches” I found an “A” story, a “B” story (with its own sub-plot), a “C” story, a “D” story, an “E” story and, incredibly, an “F” story.

The “A” story is: Dr. Orpheus has, for some reason, vaulted from the backwaters of “down-on-his-luck necromancer with no job renting Rusty’s garage” to “leader of superhero team with his own private island.” Apparently he, like Rusty, was once quite the thing, but, like many men, found himself burdened and diminished by marriage, fatherhood and responsibility. Wife gone (why is unclear, although at this point of the show literally anything is possible) and daughter of age, he suddenly “qualifies” for an arch-villain, to be supplied by the Guild of Calamitous Intent. (Why the Guild exists, how it operates, and why Dr. Orpheus suddenly qualifies is unclear, but I’m sure time will tell.) He gathers up the members of his old team, The Order of the Triad, and auditions arch-villains.

The “B” story, I would say, is Rusty and his Walking Eye (glimpsed in the season 1 titles, it now has its own plot-line). He’s built a useless machine and is bitterly frustrated when no one recognizes its brilliance. Rusty also takes time out (because the episode is, apparently, not plot-heavy enough) to chat with Dean about the birds and the bees, a chat that leaves neither one any more enlightened than before.

The “C” story involves the Monarch’s Henchmen and their attempts to, on what apparently is a slow day in Monarch-land, branch out into supervillainy themselves. Comedy ensues.

The “D” story involves a homely prostitute and her sad misadventure at the hands of The Monarch, who, after receiving his pleasure (whatever that is), turns into some kind of Thomas Harris villain on her and forces her to undergo a series of life-threatening tests in order to leave his cocoon. An Edgar Allan Poe quote is thrown in for good measure.

The “E” story involves Hank and Dean solving the Mystery of the Bad Smell in the Bathroom (and the disappearance of Triana).

The “F” story involves Torrid, who looks like a cross between Deadman and Ghost Rider, his misadventure in the bathroom and his attempts to impress Dr. Orpheus and Co., bringing the plot full-circle.

The title is “Fallen Arches” but it could have just as accurately been “False Impressions,” as each character in the episode is trying to impress someone, and often failing. Rusty wants to impress his family with the Walking Eye but fails, so instead tries to impress the Guild creeps auditioning for Dr. Orpheus instead. This works to some degree, but not without Rusty debasing himself with his Whitesnake-music-video/Tawny Kitaen “washing the car” vamp. And finally Rusty must face the fact that he has impressed no one in his house, that his inventions, his career and his life is a failure, even while Dr. Orpheus is in re-ascendency. The auditioners are desperately trying to impress Dr. Orpheus and company, and mostly desperately failing. The Henchmen want to impress some ideal, invisible female and get nowhere near even failing. The Monarch wants to impress the prostitute and does, in a way, but probably not in the way he’d like to. Dean wants to impress Triana but fails to even get her attention, although he does succeed in impressing Hank, later in the show, with his ability to actually solve a mystery. Finally, Torrid succeeds in impressing Dr. Orpheus by kidnapping his daughter, although how exactly he accomplished that, and how she ended up on Dr. Orpheus’s private island, is left unclear. I’m unfamiliar with Lady Windermere’s Fan but I’m willing to bet its plot revolves around someone trying to impress someone else too.

Who is not trying to impress anyone in this episode? Well, Brock is perfectly comfortable in his skin and doesn’t care about impressing Dean with his abilities to deliver Wilde. He’s just as happy to kill Guild villains in a tux as he was to kill them while naked a few weeks ago. The prostitute doesn’t seem too concerned about impressing the Monarch although she gives it the college try. Dr. Orpheus’s team seems quite self-effacing and comfortable with themselves, and Dr. Orpheus, with his newfound status as superhero, himself seems more confident and relaxed in this episode than ever before. Triana, of course, is a goth chick and so is genetically incapable of trying to impress anyone. Sadly, Dr. Girlfriend is briefly reduced to trying to impress Dr. Orpheus as the hastily-considered Lady Au Pair. It doesn’t take much for her to regain her self-esteem however, Jefferson Twilight’s mention of her deep voice is all it takes.

Any one of these plot lines would have been enough for most shows. This episode had the breathless pace of the Christmas special but was twice as long. It makes me wonder, aloud, what a Venture Bros feature might be like. Could this kind of pace be sustained over 90 minutes? Would there be 18 different plot lines? Would it be like It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, but funny, and short?

The Guild exists, apparently, because all superheroes require an arch-villain. Otherwise how would we know they’re heroes? It wouldn’t surprise me to learn that the Guild is financed by superheroes themselves. My son Sam understands the concept and he can’t even read; he knows that Dr. Octopus fights Spider-Man, Mirror Master fights The Flash and Sinestro fights Green Lantern. When he sees a character he doesn’t know, before he asks “What does he do?” he’ll ask “Who does he fight?”

Reagan understood that every superhero needs an arch-villain, and so does George W. Bush, although Bush made the poor decision to go for the “better Bad-Guy Plot” instead of going after the real villain. The American people have begun to understand that if you’re Superman, you fight Lex Luthor, not the Mad Hatter.

Venture Bros: a closer look

![]() mcbrennan posted this lengthy, well-considered analysis of The Venture Bros in response to my entry on last week’s “Victor-Echo-November” episode. I thought it was worth bumping up to a new entry. She starts with quoting a paragraph of mine, then heads straight into the core of the show, which becomes more interesting the more you examine it.

mcbrennan posted this lengthy, well-considered analysis of The Venture Bros in response to my entry on last week’s “Victor-Echo-November” episode. I thought it was worth bumping up to a new entry. She starts with quoting a paragraph of mine, then heads straight into the core of the show, which becomes more interesting the more you examine it.

Take it away, Cait:

“In a way the whole show is about arrested adolescence, with each character presenting their own take on the concept, and that includes Mr. Brisby. Hank and Dean are the most clinical and literal of Team Venture, being seemingly unable to make it out of adolescence alive. Dr. Venture’s more mature self literally made its break from his body to go live on Spider-Skull Island (or is Jonas his less mature self, living his playboy lifestyle?). Phantom Limb may be a sophisticate, dealing in bureaucracy and insurance and masterpieces of Western art, but in a way there’s more than a touch of Felix Unger in him, a fuss-budget who uses his sophistication to hold the world at arm’s length so that he doesn’t have to deal with the messier aspects of adult life, like maintaining a stable relationship or taking responsibility for his actions.”

There’s so much truth to this. I’m not sure if it’s arrested adolescence or just pervasive failure–failure to live up to impossible standards or to fulfil early promise, especially. Whether it’s Rusty’s boy-adventurer pedigree, Billy’s boy-genius, Brock’s football career, or the Monarch’s blueblooded trust fund origins, so many of these characters were destined for greatness and got stuck. Another specific theme I connect with is how the…the knowledge and expertise and talents of all these characters are essentially useless outside their insular little world of adventuring and “cosplay” (or costume business, in deference to the Monarch); the 60s/70s backgrounds and social “rules” are no accident. The world they learned how to live in has passed them by; The idealism of the original Team Venture is as obsolete as Rusty’s speed suits. Brock’s cold war is over; even his mentor has left it all behind, including his gender. The Guild is in league with the police. Faced with the prospect of trying to make normal human connections and fit in with the contemporary world we know (if such a thing even exists for them), Dr. Venture, the Monarch and company instead spend their time riding the carcasses of the dead past, reenacting costume dramas to keep them from going insane with boredom or despair. The scale of their “adventures” is telling: There are no world-changing inventions and no world-domination schemes. And for all the Marvel-inspired costumed supervillains, there arealmost no heroes left, certainly none in costume (outside of that ethically dubious blowhard Richard Impossible, whose entire empire sits on the rubble of Ventures past). I think that’s one of the reasons that Brock in particular can be so emotionally engaging–he’s the heart of the show, trying to hold the universe together as it spins off its axis, protecting the family he loves and trying to safeguard the next generation so that someday, things will be different. He lives by a code of honor, something maybe only the Guild still recognizes. Orpheus plays much the same role for Triana, though she and Kim are more a product of our world, and more able to see the Venture family and their nemesis as anachronisms. Triana feels for the boys, but she won’t end up like them. We hope.

Interesting also that in this world where family is so key, all the mothers are missing (Hank and Dean’s? Rusty and Jonas Jr’s? Triana’s? The Monarch’s? Just for starters…) Interesting also that the strongest female character on the show may or may not have arrived at womanhood through unconventional means, and we certainly know that the man who was like a father to Brock is now more of a mother-figure (of course, the transgender thing may be just a red herring where Dr. Girlfriend is concerned, but leave me my illusions.)

As a more or less failed child prodigy myself, I feel for these characters even as I fear I’m probably going to share their fate. I suppose sitting up at 3am writing a 5000 word essay on a cartoon is not going to change that. 🙂 But the Venture Bros. is of course much more than a cartoon, and I’m not kidding when I say it’s the best show on television. It’s a privilege to live in a time where you get to experience firsthand something that is both great art and great fun in pop culture. There’s so much going on here, so much to think about, that it’s just a delight to watch every week.

Venture Bros: Love Bheits

Random thoughts while tripping through the fragrant copse of tonight’s episode:

*The guy at the beginning of the show, standing on the volcanic landscape, turns to the camera and, for the aide of the illiterate, announces “Underland,” with a gesture as though he were ushering us into a swank restaurant. More establishing shots should be like this. I’d love to see a shot of Central Park, with the Empire State Building in the background, and a title that says “New York City,” and THEN have a guy, a cab driver or homeless guy, come on screen and say “New York City,” with the same kind of maitre-d gesture.

* Just yesterday I was thinking to myself, “I wonder where you would go to get a Slave Leia costume?” (The answer, for those interested, is here.)

*Oh hey, Luke and Leia are twins, just like Hank and Dean! And I have a feeling that Hank and Dean may not have yet met their “real father” yet either.

*So, wait. I don’t get it. You can say “Chewbacca” in an episode, but you can’t say “Batman?”

*Little miniature timberwolves. Are they bred that way, or do they naturally come in that size in Underland, perhaps because of the lack of food available? Or are they, shudder, timberwolf puppies?

*I was delighted to see Catclops, Manic 8-Ball and Girl Hitler again. I wish we had seen that Manic 8-Ball got a position in the new government at the end. Don’t tell me he died in confinement! The “tiger bomb” couldn’t kill him!

*The “cat hair in the glass of drinking water” beat took two viewings to land for me. The first time I just went “Huh?” when the Baron drinks the water and gets a weird look on his face. And sometimes the dialogue goes by so fast it takes me two or even three viewings just to catch all the lines.

*Brock’s tender mentoring of Hank makes me think, again, that Brock and Hank have a relationship that perhaps even Dr. Venture doesn’t know about.

REFERENCES I CAUGHT:

Return of the Jedi (obviously), my favorite shot being the one where Girl Hitler adjusts her mask so that her moustache can see, an exact parallel to where Lando does the same thing.

Die Another Day for the shots of the X2 being forced down by super-magnet, with pieces breaking off and flying away.

Empire Strikes Back with the thing Underbheit lives in, and the shot of the toupee being lowered down on a thoroughly unnecessary apparatus to attach itself to his head.

Fantastic Four and Underbheit’s taste in the hooded robes of dictators of fictional Eastern Bloc nations.

Simpsons Comic Book Guy for “Lamest. Villain. Ever.”

Dr. Stranglove for ![]() urbaniak‘s “German Guy” accent on the henchman who can stop tonguing the slit (boy does that sound dirtier than it is).

urbaniak‘s “German Guy” accent on the henchman who can stop tonguing the slit (boy does that sound dirtier than it is).

Sin City for the row of women’s heads mounted to the wall.

Silence of the Lambs for the shot of the fingernails imbedded in the chair arm.

All this, and a sly comment on gay marriage too. Bravo!

Found this.

The Venture Bros: Escape to the House of Mummies, Part II

The boys continue to warp and shatter the structures and expectations of form. It was funny enough that they put a fake “previously on The Venture Bros.” at the top of the show, but then they put a fake “next week on The Venture Bros.” at the end. So we’re apparently watching the second act of a three-part episode, what would in normal circumstances be released on DVD as The Venture Bros. Movie.

What makes this monkeying with structure great, of course, is the way it frees up the writers’ creativity. Why bother explaining how the boys got into the room with the spikes, or how Dean’s head got removed, or how Edgar Allen Poe got roped into this mess — that was all explained in Part I. And how will they get away from the bad guys, what will happen to the second Brock, how will Dean’s head get put back, all that will be explained in Part III. Right now, we’ve got the tumultuous, everything-in-motion Part II.

Of course, all that motion and calamity is the “B-story” this week. In the foreground is Rusty’s childish contest with Dr. Orpheus. The science/religion conflict that sparked in Episode 1 explodes into flames here, continuing Season 2’s theme of taking background ideas from Season 1 and making them the foreground here. Rusty abandons his family and tortures his friends, Dr. Orpheus fools his daughter and puts her into a coma, all for the sake of this contest. The goal of the contest? “Who can be the smallest,” of course, again, making the metaphoric literal. And when they both lose, they only do so because they both win! They’re both the smallest men!

And while it’s true that Orpheus is a know-it-all, I too felt the urge to correct the deity when he made the mistake of confusing Argos and Cerberus.

I once wrote for a comedy show, and the sketches for the show were developed as though the show were taking place in the late nineteenth century and were being written for the vaudeville stage. The producers insisted that each sketch must have a premise, development of the premise, a satisfying conclusion to the premise (called “the payoff”) and then a final “switcheroo” that they called “The Button.” This strict adherence to 100-year-old comedy rules helped ensure that every idea the writers had would eventually be turned from something everyone thought was funny to something no one thought was funny. After a few weeks of observing just how deadening this process was, I raised my hand in a meeting and said “I’m sorry, didn’t Monty Python prove, twenty-fiveyears ago, that you don’t need any of this crap? Why can’t we just think of funny ideas, keep them going for as long as they’re funny, then cut away when they’re not funny any more? Won’t that make the show fresher, more unpredictable, cut out all this dead time, and keep all the sketches from feeling exactly alike?”

It was questions like this that have kept me from working in television comedy for the past ten years.

So it’s good to see The Venture Bros., in its second season, being so voracious in its appetite to expand the boundaries of the possible in television.

Venture Bros: Hate Floats

1. Great title, and illustrative. The characters are separated and teamed with enemies and strangers, and find unlikely alliances due to the only thing they share: a desire to destroy their enemies.

2. High level of carnage. Could be the bloodiest so far. Last week’s episode with the fourteen deaths was hysterical, but this was almost like real violence. Truly disturbing. I’ve never seen an eyeball out of its socket, animated, much less see a “point-of-view” shot of the same thing.

3. Any TV show that includes perverse references to Superman, Turk 182 and “Winged Victory” can’t be all bad.

4. Rusty buys Dean a speed-suit. It’s red. And it didn’t occur to me until they were half-way through their purchase that Dr. Venture’s suit was once red too, but he’s worn it every day of his life since he bought it as a teenager. Now it’s faded to what my old apartment building decorator called “Desert Rose.”

5. Terrific episode-long piece of sustained action. Really, everything cuts together beautifully. It’s not just funny, it’s also genuinely exciting.

6. The most important thing, the show is completely transforming itself. Last season, a good deal of the humor was the humor of disappointment, where they set up the action cliche and then deflate it by having something mundane happen. Here, they set up the action cliche and then turn it on its head, pump it up, twist it inside out, increase the tempo and turn it into something that manages to be both parody and the real thing at the same time.

7. The sustained narrative. I cannot stress how different it makes everything.

Venture Bros: Season 2, Episode 1

Maybe I’m just buzzed, but that didn’t feel like a new episode of The Venture Bros. That felt like a completely different show. The pacing, the complexity, the multiple layers of action and interaction, all with the typically dense saturation of pop-culture references from Batman to Poltergeist.

It’s like the concepts from Season One have been folded up, crushed into a forge and pounded with a pneumatic press to form just the bones of the new season, and then there’s actually another show on top of it.

Far too much information to take in in one viewing.

It feels like the gloves have come off. The subtext has become the text. It’s no longer hinting at ideas or alluding to them, it’s coming right out and saying “This show is about ideas, and then it has to be funny, and then there has to be some kind of adventure plot.”

Startling to see a half-hour comedy, especially an irreverent, scatological half-hour comedy supposedly produced for an audience of teenage stoners, suddenly go from episodic television to mega-narrative. The mega-narrative was always there, but it felt like if the Sopranos had started out like, say, Law and Order and then suddenly turned into the soap opera that it is.

The science/religion argument that goes by in an instant, a dozen multiple deaths in ten seconds, a prison break, introspection, a drug-laced pacifier, a jungle babe, zombies, the monarch’s makeshift costume, the look on Dr. Girlfriend’s face as she gazes longingly out the window, and that covers maybe a sixteenth of the moments that make this dizzying, electrifying television.

Special kudos to the voice work, specifically Mr. Urbaniak’s newly confident reading of Jonas Venture. It’s great to see a show not sit still but rather unfold in a dozen delightful, unpredictable ways.

Curb Your Enthusiasm

This is the best written, best acted, best executed American situation comedy since All in the Family.

Oh, I know, there was another well-written, well-acted, well-executed show somewhere in there, a little bauble called Seinfeld, but I honestly see Curb Your Enthusiasm as the more refined, better-formed show.

Legend has it that The Dick Van Dyke Show originally starred Carl Reiner, and that a pilot with him as the star exists somewhere. I think if that show had gone forward as planned, it might have turned out something like Curb Your Enthusiasm.

The show has its drawbacks. For instance, if I want sex from my wife, we cannot watch Curb Your Enthusiasm before bedtime.

Three different times, American television has tried to re-make Fawlty Towers, once with Harvey Korman, once with Bea Arthur, and most recently with John Larroquette. I don’t advise against a fourth attempt, but if they should want to try it again, Larry David could be their man. He doesn’t have anything like Cleese’s towering presence or exquisite physicality, but no one else currently in American TV can be as unapologetically unpleasant as he is and still have the audience on his side.

Venture Bros. miscellaneous

In the pilot, I love how The Monarch has, in addition to his antennae-like eyebrows, another pair of pretend antennae on his crown. As though to say, “Look how evil I am! TWO PAIRS OF ANTENNAE!”

In the Christmas episode, it’s a true pleasure to hear James Urbaniak recite the most faithful, and yet most demented, version I’ve ever encountered of the climactic scene from A Christmas Carol. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that one of the key pleasures of this show is how it is incredibly faithful, even fannish, about its source material, while simultaneously gutting it in the most disrespectful ways.

The pilot is interesting mostly to see how the characters aren’t quite there yet, how the timing and feel of the show, its balance of elements, developed and matured over time. Given the rapid rise in quality from the pilot to the first episode, I can’t wait to see what happens in Season 2.

The Christmas episode is so packed with incident and ideas, presented at such a breathless pace, it almost makes me wish more shows were done in 11-minute segments, like Spongebob is. Maybe there could be more 11-minute Venture Bros. pieces, ideas that are funny but won’t sustain a 23-minute narrative.

Worth it for the “Tiny Joseph” character, and the moment when Hank says “Uh-oh, baby Jesus is out of the manger!” and Brock habitually checks his fly.

I was sad to see Baron Unterbheit kill off his henchmen with the Tiger Bombs. I really wanted to see the further adventures of Cat Cyclops, Girl Hitler and Manic 8-Ball.

Venture Bros: Ghosts of the Sargasso

Hands down, my favorite episode.

Why? Starting with the head-spinning Bowie intro (what is it with these guys and Bowie? Except that Bowie always had the air of a Bondian super-villain about him) (seriously, why hasn’t Bowie been made a Bond villain yet? Chris Walken has, Jonathan Pryce has, why not Bowie?), then moving from 1969’s “Space Oddity” across the pond to 1969’s “Scooby Doo” and the ghost pirates. Having young children, I’ve seen the ghost pirate episode of “Scooby Doo” several times now, so this parody has especially sharp teeth for me.

Then there’s things like the treatment of the colors in the “1969” footage, and the quite-subtle dirt and scratches on the film, not over-played, not drawing attention to itself, beautifully done.

But mostly, it’s the script, or rather, the plotting. I think this is the most tightly-plotted of all the episodes. All of the episodes use the collision of “exciting adventure” and “prosaic real-life” to produce laughs, but usually they do it in terms of “adventure that doesn’t happen.” The assassination attempt fails, so the henchmen have to wait around in the yard. The torture victim has a medical condition, so the torture has to be put on hold. It’s about dashing expectations.

But here, there’s an actual adventure. Rusty is actually going to try to do something (retrieve his father’s spaceship), and his actions have consequences (unleashing the ghost of Major Tom). Meanwhile up above, the ship is taken over by “ghost pirates,” who turn out to be real pirates.

Now there’s a twist! Ghost pirates that turn out to be not part of a real-estate scam, but REAL PIRATES! Even if they’re lame pirates, they are actually still real pirates, and they even manage to get the better of Brock.

And then there’s Brock. Brock, who specializes in getting out of impossible situations, gets out of a doozy here. I’d like to think that the actual fight with him and the pirate henchmen, where he clubs one to death with the body of the other, while the other’s arm is still up his ass, was filmed but cut, and exists somewhere in a vault. But that’s probably only a dream.

Two actual exciting events going on, Rusty stuck at the bottom of the sea, slowly dying, and Brock turning the tables on the pirates above, PLUS Hank actually turning into a capable action hero (with coaching, of course), all played out in an exciting, albeit highly comic cutting style.

Then the REAL GHOST shows up, and by this time we’re so off-balance, we’re ready for anything. So when it turns out that the ghost isn’t interested in killing anyone, hurting anyone, or really doing anything but re-living its dying scream over and over again, PLUS there’s the great bring-back of “The Action Man” from the pre-credit sequence, it’s just too laugh-out-loud, alone-in-your-living-room funny.

The ending, where Brock simply tears the ghost limb from limb and tosses it overboard, reminds me of the old Jack Handey “Deep Thought:”

“If trees could scream, would we be so cavalier about cutting them down? We might, if they screamed all the time, for no good reason.”

This is, of course, the casual cruelty that I’ve mentioned before that gives the show its misanthropic bent. We start the show with a real (if comic) tragedy, we produce the screaming ghost of that tragic figure, and there’s that moment of actual pain and anxiety where we feel that ghost’s pain. The tragedy of the past is literally brought to the surface and shoved in our faces. And how shall we deal with it? Dr. Orpheus’s plan doesn’t work. And the ghost doesn’t want to hurt anyone. But it won’t stop SCREAMING. So let’s let Brock tear its head off and throw it overboard. Good riddance.

Pirate Captain: “Well, we could have done that.”

Question: They call Dr. Orpheus for help, but then in the episode where they first meet Dr. Orpheus, Hank (or Dean, I can’t remembe their names) says to Punkin that they’ve recently battled ghost pirates. Did they battle ghost pirates twice, and why were we denied that episode?