Notes from a visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC, part 2

The Met has a ginormous selection of Greek and Roman artifacts. What I don’t know about Greek and Roman artifacts would fill a museum, one even larger than this. But the stuff on display is intriguing so I wade in. Funeral urns, columns, lots of statues of soldiers and boys and ladies, all naked. Glass cases full of cups and bowls and signet rings and necklaces and stick-pins and cutlery and weapons and plates and all manner of stuff, going on forever. It’s a morass.

Read more

Query

For instance.

For a television show I’m developing, I request your favorite instantly identifiable cultural artifacts. “American Gothic,” “The Mona Lisa,” “Guernica,” “Starry Night,” that level of media saturation.

The point of this exercise is to find works of art that anyone at all would recognize and understand to be valuable cultural landmarks. I have a running list of my own but I’m curious to see what others come up with.

Oh, and one other thing: the artifact must be portable, which leaves out DaVinci’s “Last Supper,” the cathedral of Notre Dame and the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Points awarded for not being blindingly obvious.

The artifacts selected will be made into maguffins in order to drive a mystery narrative.

Let me hasten to add that the artifact need not necessarily be an artwork. It could be a cultural artifact of another sort. Just as everyday Greek tableware items from ancient times are now considered precious antiquities and put on display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (more on that later), what other museum-quality items could one present as a maguffin in a mystery narrative? Say, the Liberty Bell, or the Wright Bros airplane.

Notes from a visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC, part 1

Greeks: excellent

Romans: excellent

Etruscans: meh

Cypriots: ugh

Persians: I don’t get it

Egyptians (pre-Rome): A plus

Egyptians (post-Rome): B minus

Rembrandt: good

Vermeer: good

Ingres: good

Goya: okay

Van Gogh: good

Gauguin: okay

Sargent: good

Degas: good

Renoir: sucks

Homer: meh

Eakins: okay

Remington: beneath contempt

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

A charming fairy-land of playfulness, whimsy and possibility, and the interior of Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory.

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is a richly realized, imaginatively produced meditation on art, creativity and irrationality, and how those unpredictable, untameable, wild qualities can be used to make a lot of money. In this regard it is a summation not only of Tim Burton’s career but of the movie business in general.

Early on in the movie, a story is told about Willy Wonka building a chocolate palace for a vain Indian prince. Wonka warns the prince that the palace won’t last, but the prince disdains his advice; eat his beautiful palace? The idea is absurd. Sure enough, the palace melts and the prince is left with nothing. This anecdote sets the tone for the rest of the story — Wonka built the palace to be consumed and destroyed, but the prince wants it to stand as a tribute to his own extravagance. Wonka knows that the power of his art lies in the fact that it will not, cannot last; the prince demands that the art last forever.

Charlie wants to get one of the golden tickets that will admit him entrance to the mysterious, magical factory — that is, he wants access to the creative center, the act of creation. A budding artist himself (he’s built a model of the factory out of deformed toothpaste caps), he seeks the locus of inspiration. Since Charlie is a desperately poor child, how shall he obtain this ticket?

The other children get their tickets through a variety of methods: Augustus Gloop gets his because he naturally eats a great deal of chocolate, Veruca Salt forces her father to enslave his factory workers into unwrapping millions of chocolate bars, Violet Beauregard gets hers seemingly through blind determination to win, and Mike Teevee gets his through “cracking the code,” using a complicated formula to determine where the next golden ticket might appear. Of these approaches, Augustus’s seems to be the most innocent and related to the natural function of chocolate (that is, to be eaten); Augustus’s problem seems to be that he enjoys his natural state a little too much.

How shall Charlie get his ticket? His parents buy him a bar for his birthday, but there is no ticket there. So parental love, generosity, legacy, inheritance — those won’t get Charlie what he wants. His grandfather gives him money from a secret stash, his last money in the world, to go buy a bar, but that bar contains no ticket either. So faith and lack of caution won’t work either. No, Charlie gets his golden ticket through sheer dumb luck — he finds a ten-dollar bill in the street (in England, but let’s set that aside for now), and buys a bar from the first newsstand he comes to. He uses no system and has no determination — he’s not a “special child,” he is not blessed. As Willy Wonka says when he meets Charlie, “Well, you’re just lucky to be here, aren’t you?”

After getting his golden ticket, after achieving his entry into the heart of inspiration, Charlie is tempted to sell out. His family, he reasons, could get thousands of dollars for the ticket, he shouldn’t be so foolish as to trade a day of inspiration for months of sustanence. His grandpa George sets him straight, tells him that money is the most common thing there is, they’re always printing more of it, but the golden ticket is rare and precious, almost unique, and so Charlie narrowly avoids losing his inspiration for something as banal as comfort.

The first stop on the tour is Wonka’s own center of creation itself, a virtual Garden of Eden of candy (the Eden parallel made explicit by Violet greedily snatching a candy apple off a tree — and lest we forget, “inspiration” means to have God breathe into you). Wonka, like God, invites the children to eat anything they want with one exception. Set free in Eden, Mike Teevee destroys as his father (who bears an uncanny resemblance to renowned subway vigilante Bernard Goetz) looks on helplessly and Mrs. Gloop is seen stealing what is being given away for free. Augustus breaks the one rule set down and gets expelled from Eden.

This is the third time I’ve watched the movie, but only the first time Johnny Depp’s performance made any sense to me. This time around, I was struck by when his speech is fluid, when he has trouble expressing himself and when he actually must rely on pre-printed cheat-sheets to say something. Since Wonka makes and sells candy for a living, it is assumed that he is a wholesome, child-friendly man, but of course nothing could be further from the truth.

The imitation “Small World” robot puppet number, meant to herald the arrival of Wonka, backfires and melts down as it invites the guests into the factory. It’s an imitation “Small World” number because Wonka is trying to match his public image as a children’s entertainer, a la Walt Disney. It melts down because it cannot disguise the fact that he is not. It’s notable for being an introduction to a character who, of course, turns out to not be part of the introduction. Wonka is happy to put on the show, but it does not occur to him that he would actually be introduced by his own introduction. That would make too much sense, and Wonka is not capable of making sense.

Little Wonka says makes sense in any practical sense of the term, and that is of course the point, or rather the pointlessness. (“Why is everything in this factory completely pointless?” complains Mike Teevee. “Candy doesn’t have to have a point,” answers Charlie, “that’s why it’s candy.”) I am reminded of conversations I’ve had with artists where I’ve tried to get them to give up the secrets of their work. They can rarely explain why they chose one concept over another, get vague and visibly uncomfortable when pressed, and either completely shut down (as Wonka does several times in this movie) or else start reciting reams of incomprehensible theory they remember from art school (which is what Wonka has the cheat-sheets for). Wonka doesn’t have a scheme or a formula or a plan; he just is.

(The most controversial aspect of the movie is its attempt to “explain” Wonka, which Burton and Depp put over in the most ironic, eye-rolling terms possible. “Okay,” they seem to be saying, “we’ll give you ‘meaning,’ but we’re not going to mean it.”)

Several things in the movie stick out amid the elaborate production design and the sumptuous photography. First is the performance of Deep Roy as every Oompa-Loompa in the movie, which is both a triumph of special effects and a triumph of acting, insofar as one quickly accepts the idea of thousands of Oompa-Loompas living in the factory and quickly forgets the fact that they’re all being played by the same guy. Second is the makeup, which seemingly transforms several of the characters into something a little more than plastic and a little less than human. Third is the trained squirrels, another special-effects triumph and the result of thousands of hours of squirrel training.

A couple of winters ago, the artist Christo finally got to install his “Gates” project in Central Park for two weeks in February. He had been trying to get it installed since 1979 and finally succeeded in 2005. There was a great deal of resistance to the project (over 25 years of resistance, in fact), both before it was put up and afterwards. I remember walking through Central Park amid the gorgeous, inspiring, completely pointless saffron banners, and being accosted by a total stranger, an older man who was furious, furious that this artwork had been put up. “Why couldn’t they use the money for something useful?” he demanded to know, from me, for some reason. To which I said “What does it matter? It was his money, he can do what he wants with it.” “Yes,” said the man, “But we have to pay for it!” To which I said “But we don’t have to pay for it. Christo used his own money to put it up, paid all the workers to maintain it, and will pay to have it taken down. In addition, he’ll pay to have the park restored to its previous condition and make a large donation to the Central Park Conservancy. In addtion, the tourists coming into the city to see the piece will bring more money in, so not only are we not paying for it, we’re in fact making money off it.” But the man would not be placated. He knew, he knew that Christo had to be making a fool out him somehow, that there had to be some kind of a scam to it, one doesn’t just spend millions of dollars on something as pointless as, as this.

I walked on through the park and came to the Sheep Meadow, where hundreds of New Yorkers and tourists roamed in a state of weird, elevated giddiness. The park had been transformed into a wild playground of irrationality; the Gates, finally, didn’t “mean” anything at all. If anything, they removed meaning from the park; they were a meaningless hoot, a shout of joy in the chill February air (I wonder if it’s symbolic that Charlie visits Wonka’s factory on February 1st, literally the middle of winter). Three years after 9/11, New Yorkers defied depression with an embrace of the exuberantly irrational. Like the palace Wonka made for the Indian prince, “The Gates” didn’t last long, by design. If it had stayed around forever, or had been brought back for an encore, it would defeat the purpose of the piece, which is to be transitory and as sensual as a bite of chocolate. To keep “The Gates” around would be to want to have one’s cake and eat it too.

Brice Marden update

There’s a piece in the recent New Yorker about the Brice Marden show at MoMA that, unsurprisingly, is more coherent and better written than my own thoughts.

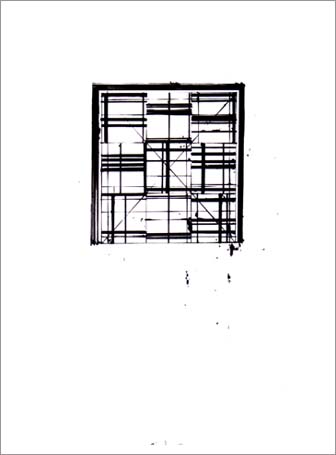

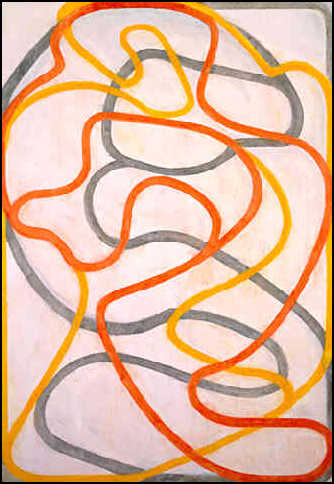

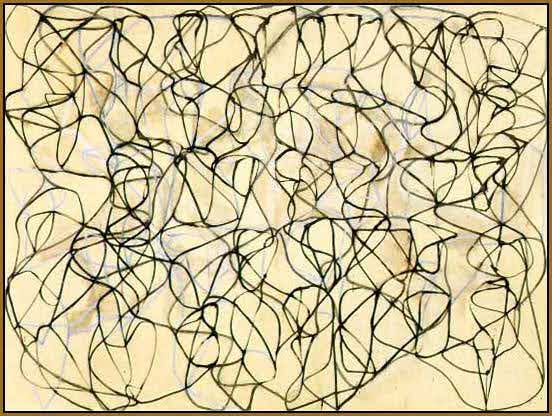

Brice Marden

Brice Marden, America’s greatest living painter, has what I believe is his first full retrospective of his work showing at MoMA right now through mid-January.

If you care anything about abstract art or American painting, or if you have a soul, I encourage you to see this show.

Yes, that’s right, when I’m not dissecting TV shows, writing movies about talking bugs or watching movies about futuristic utopias, I can often be found strolling about the world’s institutions of modern art, searching for dramatic collusions of lines and colors.

I was not always like this. I used to think abstraction was a fraud. I didn’t “get” it, I thought the artists were either delusional, working under an exaggerated or even fabricated sense of their own importance, or else laughing at us as we gazed in confusion at their messageless works.

Brice Marden changed all that.

I still remember quite clearly when it happened. About 10 years ago I was in Cambridge with my bride-to-be and I stopped in at the local art joint to see a couple of Sargents they had on display. I never got as far as the Sargents because there was a show of Brice Marden drawings on the first floor. They were opaque and confounding, yet lyrical and intriguing at the same time. They were, I found out, drawn with anything but a pen — Marden will use twigs or shells, dipped in ink and held at a distance, to keep his line naive and undisciplined — and utterly bewitching. They looked like trees or vines or hedges or something, but they were both that and not that; they were both representative of things and also just marks on paper. And suddenly I “got” abstraction. In fact, I suddenly understood what the word “abstraction” means.

And the floodgates were opened. Suddenly I “got” Pollock and DeKooning, Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter, Barnett Newman and Cy Twombly (O! Cy Twombly — for added value, there are also a half-dozen crucil, essential Cy Twomblys hanging in the Big Gallery space at MoMA). And I went from being a guy who thought abstraction was a fraud to being a guy who now can barely tolerate representation — I keep thinking a representational artist is trying to sell me something. And now I’m the kind of guy who drags reluctant friends and family to places like the Dia Center in Beacon NY to see Richard Serra’s Torqued Ellipses (I’m still cursing myself for not getting to Houston for the Twombly show a few years ago). Now I’m the kind of guy who stops to look at a crack in the sidewalk or a badly-painted wall or a carelessly-whitewashed window. For me, a painted surface is now filled with light, a line brings in drama and a whole bunch of lines, artfully arranged, can produce an almost unbearable tension.

You may hate the Marden show. When I was there today there were plenty who did. Galleries were dotted with confused middle-aged women and disgusted middle-aged men, wavering between not being sure if they were being conned and utterly sure they were being conned. The men were particularly angry about it, sniggering to each other, voicing their moral superiority, muttering threats to the artist and, in one case, even wishing him a violent death. I’m not sure what provokes a reaction like that, I don’t know what one is expecting when one comes to the Museum of Modern Art. It seems to me that someone who sees a show as positive, life-affirming and glorious as this and reacts with a wish of violence upon the artist probably shouldn’t bother walking into an art museum in the first place.

UPDATE: Thanks everyone for writing in. For the folks who hate this stuff, let me reiterate, I used to hate it too. Now I don’t and this guy is the reason. I’m not an art historian, I’m not a theoretician and I’m sure as shootin’ ain’t no elitist. He opened up a whole new artistic world for me and I’ll never forget it.

And for those who like this stuff, here’s a few more. Thanks again!