The Etruscan Horse

Some thoughts on the screenplay for Oppenheimer

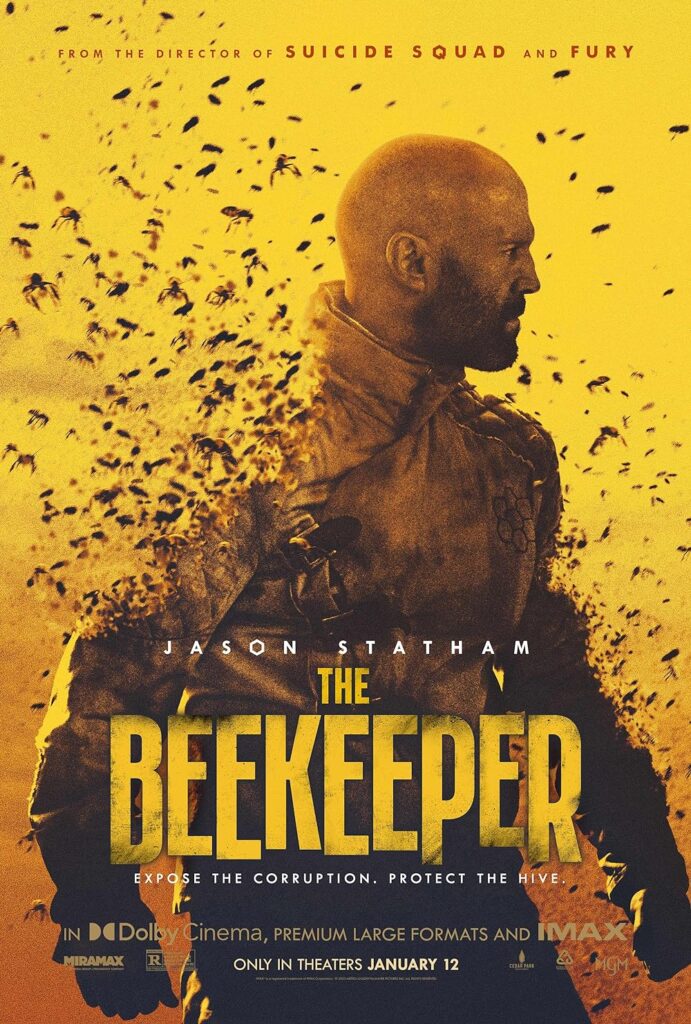

The Beekeeper

When I was in my 20s I managed a movie theater on 59th St in New York, the Manhattan Twin. It was part part of the City Cinemas chain, which was a clutch of theaters that had been built on the ruins of Dan Rugoff’s bankrupt Cinema 5 theater chain. City Cinemas’ flagship theater, Cinema I, was right around the corner from the Manhattan Twin, but the difference in programming could not have been different. Cinema I would show a movie like Kiss of the Spider Woman or And the Ship Sails On, while the Manhattan Twin would show movies like Police Academy or Splash. As I used to put it, “Cinema I is across the street from Bloomingdale’s, the Manhattan Twin is across the street from a deli called Meat Land.”

When I was in my 20s I managed a movie theater on 59th St in New York, the Manhattan Twin. It was part part of the City Cinemas chain, which was a clutch of theaters that had been built on the ruins of Dan Rugoff’s bankrupt Cinema 5 theater chain. City Cinemas’ flagship theater, Cinema I, was right around the corner from the Manhattan Twin, but the difference in programming could not have been different. Cinema I would show a movie like Kiss of the Spider Woman or And the Ship Sails On, while the Manhattan Twin would show movies like Police Academy or Splash. As I used to put it, “Cinema I is across the street from Bloomingdale’s, the Manhattan Twin is across the street from a deli called Meat Land.”

In the fall of 1984, the Manhattan Twin booked a Charles Bronson vehicle titled The Evil That Men Do. As the manager, it was my responsibility to watch every movie we showed, to make sure the reels were in the right order and the print was presentable. I watched The Evil That Men Do and I didn’t like it. I found it unnecessarily crass, vulgar and cheap, and its violence overly harsh and brutal. I expected it to die a quick death and be replaced on our screen by, maybe, the delightful Steve Martin/Lily Tomlin comedy All of Me.

But The Evil That Men Do didn’t bomb. It wasn’t a huge hit, but it didn’t bomb. The theater was never full, the theater was never even half-full, but the audience came, and it kept showing up. Every time we thought the box office for the picture was going to trail off, it would rally again, never enough to be a smash hit, but enough to keep it in the theater for another week. The movie had legs. Stumpy legs, to be sure, but solid, and they kept moving forward every week. The audience never dropped off, it just remained static, week after week. It opened on September 21 and we were still showing it on Thanksgiving, which turned out to be twice the movie-going day anyone in the theater chain expected it to be. We were short-staffed, because it was Thanksgiving, and we were besieged by hundreds of people all day on our two screens.

I remember, on that long Thanksgiving Day, wondering “Who are these people?” The Evil That Men Do was, at that point, in its ninth week, and here we were, packing them in on a day when everyone should have been at home with their families.

So I watched them as they came out of the movie. They were all older men, men in their late 40s, 50s, early 60s. They never had dates, they always came alone. They were paunchy and saggy, their faces lined and their eyes flinty. They were tired, worn, and dyspeptic. They were working class, dressed in windbreakers and overcoats, with sweaters or sweatshirts over button-down shirts. They were the kind of men I had never thought about for a single second of my life, cab drivers and factory workers, middle-managers and plumbers, shoe salesmen and tradesmen. And they all wanted to see Charles Bronson in The Evil That Men Do.

I don’t remember a single second of The Evil That Men Do, but I can tell you, without looking, what it’s about: a middle-aged assassin is brought out of retirement because a close friend of his has been killed, and he will stop at nothing to murder all the people responsible.

And I thought, well, I don’t like that movie, and I don’t buy that kind of macho bullshit fantasy, but look at the faces of these men walking out of the theater. They love the movie, and they have found something of value in it, and it has made them feel, for a couple of hours, less alone in the world.

Like the Grinch on Christmas Eve, my heart grew three sizes that day, and I became much more forgiving of movies I don’t like. I realized that, while they were not to my taste, that that was okay, because not everything has to be made for me. What is required is that a movie find its audience and give it what it wants.

After that, I started to watch everything we showed, in the theater, with an audience. It didn’t matter what it was, a teen comedy, a romance, a horror movie, if an audience responded to it I wanted to know why. I tossed aside whatever personal preferences I had and paid attention to what the audience was looking for, and spent a lot of time wondering why one movie bombed and another one flourished. I now remember movies from that era as much for their audience’s reactions as for the movies themselves.

The decades flew by, but every once in a while I would stop and think about The Evil That Men Do and the mysterious audience of middle-aged working-class men who turned up, week after week, to watch it, and the bond that a movie creates with its audience, regardless of the quality of the product.

I realized the men who came to see The Evil That Men Do probably felt as though they had all followed the rules set down by the Truman administration: get a job, get married, have kids, buy a house, pay your mortgage, die happy. But life hadn’t turned out that way for them. They all felt shortchanged. They all felt like they had been forgotten. Their kids had moved out, their wives perhaps as well, and they didn’t have a house, they were renting now, and their dwellings were getting smaller and smaller as Reagan’s economy handed more and more of their savings over to plutocrats. And every day, more was being taken from them, just through the process of getting old.

That audience needed a hero. They needed to see a man who was both incorruptible and indestructible, highly intelligent and and expert in both strategic and tactical maneuvers. They wanted to see a man of the highest possible moral character, a man who had been around the world and seen a lot of trouble but who now wants only to live his life in peace, who wants only the leisure to putter around his country house and engage in some kind of hobby — stamp collecting, maybe, or refurbishing a vintage sports car, or building elaborate dioramas of Civil War battles. This man would only want a quiet life where they were free to contemplate the endless tapestry of life’s mysteries, but he would also, secretly, be an unstoppable killing machine who is prepared to exact bloody revenge when he is pushed too far. This hero would talk as little as possible, his primary expression would be through motion, and any dialogue he had should be honed and polished into monosyllabic gems.

That audience was prepared to forgive a movie any amount of ludicrous plot, any number of outrageous contrivances, any display of improbable physics, as long as their stoic, had-enough hero hit his beats, dispensed unadulterated justice, and lived to fight another day.

Anyway, here we are, and it turns out I’m now one of those guys, and I thoroughly enjoyed the completely ridiculous The Beekeeper.

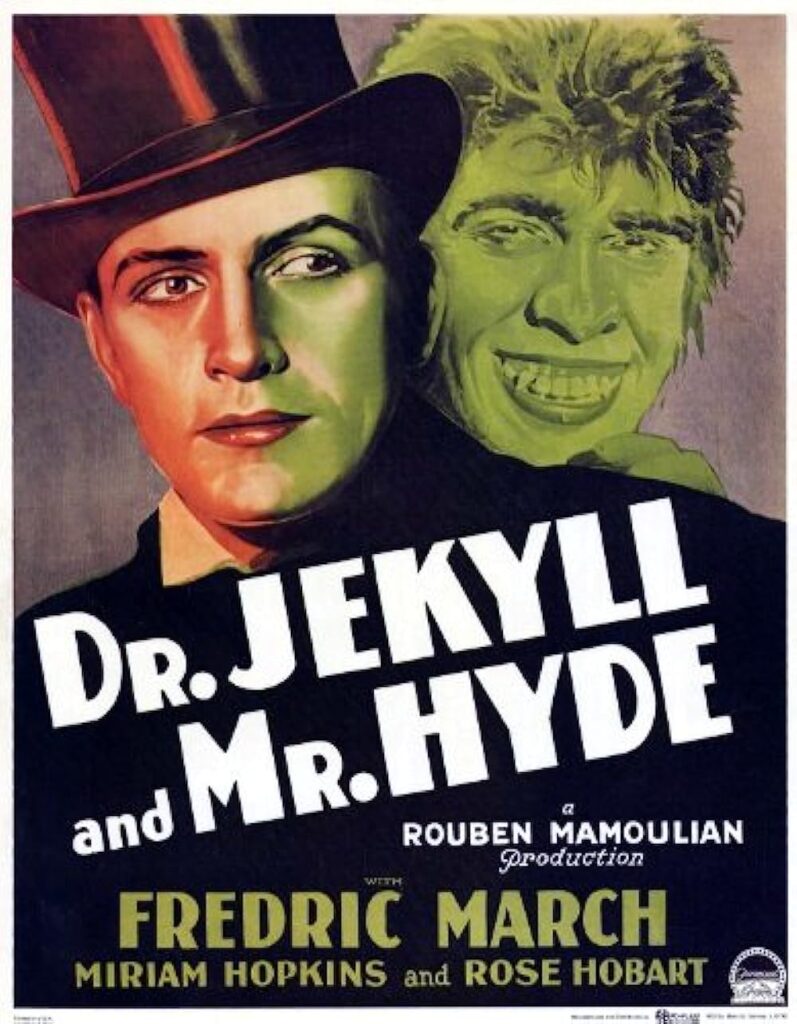

Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde

Some thoughts on Guardians of the Galaxy Vol 3

What does the screenwriter want?

What does the screenwriter want?

The screenwriter wants to get into the room with The Person Who Can Say Yes.That is the only thing that matters. Everything before that is preliminary, and, often, a complete waste of time for everyone involved.

Here is a typical scenario:A producer has optioned a piece of IP. It could be a book, a graphic novel, a Twitter account, a board game, a toy, a sticker, a photograph, anything. The producer, also, wants only to get into the room with The Person Who Can Say Yes.The Person Who Can Say Yes is someone high up in the studio food chain, someone who has been authorized to spend money to hire writers. There are very few in Hollywood, and they wield enormous power.

The Person Who Can Say Yes wants only one thing: to keep their job. Because they wield such enormous power, every other executive around them, at their studio and other studios, is constantly trying to get them fired so that they might take their job and wield that power. But that’s a subject for another time.

Between the screenwriter and The Person Who Can Say Yes are lots and lots of other people. Producers, lower-ranking studio executives, development executives, story executives, and unpaid interns, all of whom wield more power than the screenwriter.

To say nothing of the screenwriter’s representatives, who have their own agenda unrelated to the writer getting into the room with the Person Who Can Say Yes.

So the producer has a piece of IP. The producer also knows some screenwriters. That, essentially, is what a producer does: they know people. They own a phone, and a car, and they know people. Those are the only requirements for being a producer.The producer calls the screenwriter’s representatives and says “I have this piece of IP and I think your client would be a good match for adapting it for the big screen.” The screenwriter’s representatives then call up the screenwriter and breathlessly exclaim, “Big Important Producer has obtained the rights to Hugely Popular IP and he wants YOU to adapt it!”

The screenwriter can then say “Eh, that doesn’t really sound like a good idea,” or they can say “Wow, Big Important Producer wants ME to adapt Hugely Popular IP? I can’t wait to meet them!”

Maybe the producer DOES want the screenwriter to adapt it, and maybe the producer has called a dozen different screenwriters’ representatives and told them all the same thing. It would certainly make sense to do so, since some might say no and some might say yes and then fail to come up with any ideas.So the screenwriter meets the producer and they talk about the idea. The producer may have specific goals in mind for the IP, or they may have specific ideas about casting or directors or whatnot, and they’ll ask the screenwriter to incorporate those ideas into their pitch. Then they’ll set a meeting for the pitch.

So the screenwriter has to come up with a pitch. The screenwriter hasn’t been paid anything to come up with a pitch. The screenwriter doesn’t have the power to say “No, I’m not going to write a pitch for you, put me in the room with The Person Who Can Say Yes.” If the screenwriter did say that, that would be the end of his relationship with the producer, who controls the IP. The producer, like the screenwriter, wants only to get into the room with The Person Who Can Say Yes, but they’re not going to go into that room without knowing what they’re pitching, because they only get once chance to pitch to each Person Who Can Say Yes, and there are very, very few People Who Can Say Yes in Hollywood.

So the producer tells the screenwriter to develop a pitch and get back to them.

What does the pitch entail? Basically, it’s the story of the movie. Beginning, middle and end. The three acts. What does the protagonist want, what do they do to pursue their goal, what stands in their way, how do they prevail, etc. By the end of Act I, the protagonist must be headed toward their goal. By the middle of Act II, they must have a “false victory” that makes it look like they’ve got it made. By the end of Act II they must suffer a fate that makes it look as though they will never achieve their goal, and by the end of Act III they must achieve their goal or else they must fail in a way that makes the audience feel good.

So the screenwriter sketches all that out. It doesn’t sound like a lot, does it? And yet, that’s the whole movie.

So the screenwriter pitches the story to the producer, who inevitably says “I need to know more.” They need to hear the “trailer moments,” the scenes that will hook an audience into the story. They need to know the twists that will come out of nowhere and yet seem inevitable, they need to know the last-minute reveal that will shift the paradigm of the narrative. They need to present to the Person Who Can Say Yes the entire narrative of the movie.

Now the screenwriter has another choice. They can say “No, you’re asking me to write the whole movie for free and that’s abusive,” but that would end their relationship with the producer, who will never work with the screenwriter again because the screenwriter is “difficult.” The screenwriter has spent maybe a week of their life at this point working on breaking the story, but the producer likes what they’ve heard so far, why not fill in some details?So the screenwriter spends another week writing a treatment, and then there’s another meeting with the producer, where the screenwriter pitches the entire movie to the producer: all the major scenes, all the twists, all the aspects of the narrative that will hook an audience. The producer loves what the screenwriter has done, but “has some notes.” The producer confers with his assistants and unpaid interns and they put together a list of notes that they want the screenwriter to address. And, also, as long as the screenwriter has a whole treatment written, can they see that treatment so they can understand the story better?

All of this is against the rules of the WGA. And it happens ten thousand times a day in Hollywood.

So the screenwriter does another draft of a treatment for the producer. And another. And another. What choice do they have? Nothing else will get them into the room with The Person Who Can Say Yes.

Now, maybe six months have passed. The screenwriter has produced maybe ten drafts of a treatment for the producer. Every scene in the movie has now been outlined.Now, remember, the screenwriter, statistically, has no money, and has no hope of money without selling a pitch, so, in order to stand a chance of selling something to anyone, they have to have a dozen or so different projects going on at once, in different stages of development, all before they can ever get into the room with any Person Who Can Say Yes. Some of the projects will be dear to the screenwriter, some will be for movies that the screenwriter would never even want to go see, much less write. Some of the projects are with people the screenwriter enjoys working with, some are with abusive assholes who like to bully and mind-fuck people. The abusive assholes tend to get more projects made, hence their attractiveness to screenwriters.

Sometimes, for an especially high-profile piece of IP, or for an especially high-powered producer, the screenwriter’s representatives will get in on the action, demanding to read the treatments and presenting their own notes, which the screenwriter has to then incorporate into the pitch or else run the risk of alienating their representatives.The producer then takes the screenwriter to the studio, and meets with someone high up in the production chain, and the screenwriter pitches the entire movie to that development executive.

The development executive then says “I love it, let’s take it to the Person Who Can Say Yes” but, yes, before that happens, has some notes.

So the screenwriter now, again, has a choice. They can say “Fuck you, it’s been six months of me working without getting paid, I’m not working on this project for one more second without a substantial paycheck,” but then that would end their relationship with the producer and the studio executive and the studio itself. So the screenwriter says “Yes, I’d love to hear your notes,” and the development executive says “Would you mind if we took a look at your treatment? It would really help us focus our notes.”And the screenwriter turns over their treatment, and the development executive and their assistants and unpaid interns get together and put together a list of notes.

This might go on for another six months, as the development executive asks for more and more changes. And then the development executive might want to show the pitch to ANOTHER development executive, so the screenwriter and producer will have to pitch to that development executive too, and so forth. Maybe a year into the process, maybe longer (my record is two years) the big day arrives, and the screenwriter, the producer, the producer’s assistants and unpaid interns, the development executives and assistants and unpaid interns, all meet at the studio with the Person Who Can Say Yes, who has their own platoon of assistants and unpaid interns.

The producer then sets up the pitch, tells the Person Who Can Say Yes why the project is commercially viable, and then turns to the screenwriter and says “And here’s the screenwriter, who will now pitch you their ideas.” No one else in the room ever, ever, ever steps forward and says “We’re really proud and excited about this pitch that we all contributed to,” because if the Person Who Can Say Yes says no, they’re all in danger of losing their jobs. So everyone in the room who has given notes to the screenwriter and has followed every step of the process behaves as though all this is brand new to them.The screenwriter then does the pitch. The pitch must be delivered with the creativity, dynamism and force of a $200 million dollar spectacle. It must feel to the Person Who Can Say Yes that they’re seeing the whole movie there in there office.

The Person Who Can Say Yes then, usually, says no, for any number of reasons. Maybe they said yes to a similar project the day before, maybe they’re mad at the producer for some reason unrelated to the project, maybe their third-quarter projections aren’t hitting their mark and they’re afraid they’ll lose their job if they start a project like the one the producer has brought in, or maybe they don’t like the pitch. And sometimes the Person Who Can Say Yes says “I like it, but I have some notes,” and the screenwriter, once again, has a choice to make. They’ve come this far, they’ve spent a year and a half on the project, all without pay, but here they are with the Person Who Can Say Yes and the Person Who Can Say Yes has not said “No.” The big paycheck is dangling in front of them, what is the screenwriter supposed to say?

The screenwriter might go to their representatives and say “What am I supposed to do, I can’t pay rent and I’ve been working on this project for a year and a half and they’re not paying me anything, and the screenwriter’s representatives will say “Do the extra work for free,” because, here’s a secret, the screenwriter’s representatives don’t represent the screenwriter, they represent the Person Who Can Say Yes. Why? Because the People Who Can Say Yes control the entire Hollywood economy, and if an agent or manager demands something from them, the People Who Can Say Yes won’t hire that person’s clients anymore.

Anyway, that’s just one tiny aspect of what the WGA is up against in this strike, and it was my day-to-day reality for 25 years.

The first time the WGA changed my life

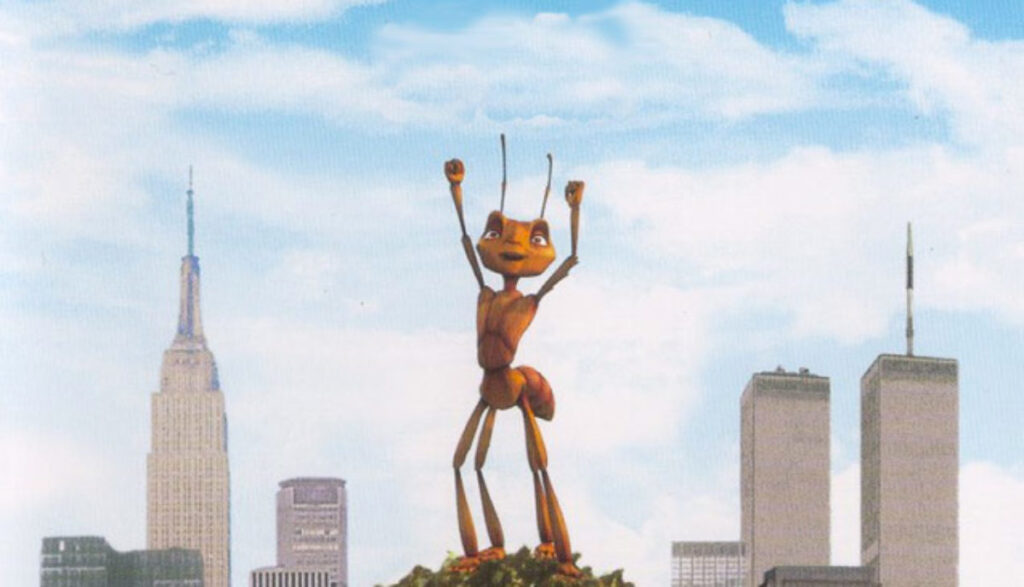

In the summer of 1995, a studio executive at Dreamworks, Nina Jacobson, read a script of mine that had gotten some attention in Hollywood, and had a meeting with me in New York. We got along great and, months later, she called me up with an unusual question: would I like to write an animated movie about talking ants?

I had never written an animated movie before, and didn’t really consider it my “area.” I was a “downtown playwright” living in a crappy apartment on 12th St in Manhattan, where prostitutes regularly waited for clients. I was “edgy.” I wrote plays about serial killers and psychic phenomena. But, I reasoned, if I was going to write an animated movie, it might as well be for Jeffrey Katzenberg, the man who had spearheaded the Disney Renaissance with the movies The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, and a little bauble called The Lion King.

Nina flew me to Hollywood and treated me very, very well. Everyone at Dreamworks treated me very, very well. I got to meet Steven Spielberg, who gushed to me about how much he loved the screenplay that had gotten Nina’s attention, a moment that I will cherish forever.

Most importantly, I got to take a master class in screenwriting, directly from Jeffrey Katzenberg, who had no patience for any writer’s indulgences beyond “WHAT DOES THE GUY WANT?” a phrase he reiterated so often, I wrote it down on a postcard and stuck it over my desk. Because, after all, that is, in fact, the only question a screenwriter should ever be asking, or answering: What does the guy (ie, the protagonist) want?

It wasn’t easy, going from being a smartass downtown playwright to efficient Hollywood scribe, and, looking back on those days, I’m consistently amazed at how well I was treated by the entire staff of the studio, how patient and kind they were to a screenwriter who, literally, didn’t understand the first thing about writing screenplays.

The early days of writing the script for Antz went like this: Nina and I would meet in the morning, talk through the story, and then I’d go write a treatment based on the conversation we’d had. When Nina felt like the story was good enough to take to Jeffrey, we’d have a meeting in his office, or we’d have a meeting with Walter and Laurie Parkes, who were also higher-ups in the Dreamworks production team. Jeffrey, or Walter and Laurie, would listen to the story and give us notes, and then Nina and I would talk over the notes, and then I’d write another treatment.

There would be occasional guest stars. The wonderful screenwriter Zak Penn had been hired on a consultant on the script (Nina had asked Zak to write the script before me, but he was busy working on another project). Zak was a big deal at the time, and was also extremely kind and patient with me as I fumbled my way through the development process. The great writing team Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio were on the staff of Dreamworks at the time as sort of free-floating story doctors, and they were also extremely kind and patient with me, sharing their wisdom and humor freely with me. Steven Spielberg sat in on a story meeting at one point and offered his own take on the material. And there were other Dreamworks executives and producers who weighed in on various aspects of the story. To say nothing of the visual consultants who were hired to create vision boards to help me in getting a better picture of the movie I was writing.

In all, I wrote 30 treatments for Antz before being given the green light to write the script. Some of those treatments were as short as two pages or as long as forty.

I was paid for none of them. Those treatments that I wrote over months of development were all just part of the audition process, the same audition process that any writer has to go through in Hollywood in order to get a job writing a screenplay.

I didn’t care, of course, I was a smartass downtown playwright who was staying at the Chateau Marmont, being fed every day by Steven Spielberg’s personal chef, dining at Beverly Hills restaurants with some of the most powerful people in the industry and having an amazing time. The studio even flew me to Chicago for a weekend because I was doing my one-man show there. They showed me nothing but respect and affection.

The day finally came, after about six months of work, that Jeffrey listened to my pitch, said “Yep, that’s it,” and then purchased, for $40 million, an entire animation studio in Palo Alto, and then put me on David Geffen’s private jet to go meet with the directors and dozens of animators who were working to bring my cinematic notions to life.

All very head-spinning stuff for a smartass downtown playwright!I was finally formally hired to write two drafts of a screenplay. I only wrote one, but they paid my contract in full. They then hired Chris and Paul Weitz, an up-and-coming screenwriting brother team, to take over for me. Chris and Paul, I should also note, were ALSO very kind to me, and were cheerful, solicitous and complimentary colleagues for the time we worked together. Chris and Paul, of course, went on to write and direct many, many fine motion pictures.

I didn’t mind being replaced on Antz. Writers in Hollywood get replaced all the time, for a variety of reasons, there’s no reason to take it personally.

Shortly before the movie opened, Nina called me to tell me that the Weitz brothers’ representatives had contacted the studio to alert them that they were seeking to have my name removed from the credits for Antz. It’s easy to see their logic: I had worked on the script for six months, and they had worked on it for two years. What’s more, they had personally worked alongside the directors and animators to best present the most coherent version of the material possible. They had worked hard on the movie, and they felt a sense of ownership. I can’t blame them, I would have too!

Jeffrey Katzenberg, to his everlasting credit, told the Weitz’s reps that, yes, their clients were welcome to challenge the studio’s credit assignment. However, although the movie was animated, and therefore did not fall under the jurisdiction of the WGA, the studio would hire a WGA arbitrator to arbitrate the credit assignment according to WGA rules.

At that point, the Weitz’s reps dropped the complaint and the movie came out with my credit intact. Because, under the arbitration rules of the WGA, they ran the risk of having THEIR names, not mine, removed from the credits. Because the WGA values, above all, the work that the first writer does. Whoever comes after the first writer of a screenplay faces significant hurdles in trying to claim the work as solely their own, under the rules of the WGA.

Just as I did not want to see my credit taken off Antz, I also did not want to see the Weitz’s credit taken off either. They did an incredible amount of work, and under the pressure of a deadline, with a million moving parts churning all around them. My hat’s off to them and all the other people who made the movie what it is. There are no villains here. But without the WGA, I would not have the one hit-movie credit I do.

Of course, I receive no residuals from Antz, because, being animated, it does not fall under the jurisdiction of the WGA.

Black Summer

A few days ago, I’d never heard of Black Summer, a Netflix zombie show that’s some sort of prequel to Z Nation, which was a SyFy zombie show, which I’ve never seen. Anyway, now I’m obsessed with it.For fans of the zombie genre, Black Summer takes everything you like from the form — tales of survival, tales of courage and cowardice, tales of savage brutality and unexpected grace, tales of corruption and greed and human frailty, and boils away everything down to the bone. There is no moralizing, there is no metaphor, there is no sentimentality, no pontificating, no speeches, no hip cynicism or critique of consumer culture. What remains is breathless, white-hot adrenaline.

Characters have backstories and personalities and all that stuff, but what they don’t have is speeches. Or, in many cases, names. Some have no dialogue at all. There are no “campfire scenes” where the characters express themselves and come to learn something about each other. Instead, we learn who the characters are purely by their actions — how do they handle themselves, how do they carry themselves, how committed are they to survival, how far will they go, what physical punishment will they endure, and how much will they mete out?

There is very little “down time” at all on the show, and very little sense of a “bigger picture.” Each scene is set apart from the others by a title card, and presents a specific tactical situation. You’re in a car being chased by a truck, and you run over a child’s bicycle in the road. Do you stop and get it out from under the car? Do you have the time to do that before the truck catches up? And if you do, who gets out to remove it? Who is the most expendable, who is the bravest, who is the fastest, who is most committed to survival? And then, what about the zombies that are running around, screaming and roaring and gushing blood from their mouths? Is there one behind that garage? Or behind that tree? If you’re the one that gets out of the car, do you trust the driver not to drive off, using you as bait, either to slow down the truck, or to slow down the zombies? There’s an episode in the first season that’s almost entirely a chase scene between a character who is not cut out to face a zombie apocalypse, and an incredibly persistent zombie, without a line of dialogue, just pure action.

David Mamet once mentioned something about audience interest — if you see two men arguing on the street about one owing the other money, you lose interest quickly. But if you see a man walking down the street, and then a car screeches to a halt and another man leaps out and charges at the first man, swearing at him and throwing punches, that will keep you interested, and want to know more about what’s going on with these two.

Black Summer operates entirely on that principle. We’re told nothing whatsoever about the characters, we just have to lean forward and pick up what we can based on how they relate to one another and how well or poorly they navigate their environment. Sometimes we see a group of people and make assumptions about who they are and what they mean to each other, only to learn later that it’s a completely different situation than we thought.

It makes The Walking Dead feel ponderous and sentimental and Game of Thrones feel squeamish. Characters show up in one scene save they day or gain our sympathy, only to turn, seconds later, into a zombie, or be killed in some errant piece of violence or recklessly driven car. Characters we admire are instantly erased from existence without a dying speech, a reverent close-up or even the camera standing still for one second.On top of all this, the scripts, which are uniformly excellent in terms of action writing, tell stories in chopped up order, as we follow characters as they negotiate an obstacle, then follow another character as they try to get into a building, then follow another character we saw in the background from earlier in the episode, then switch to an entirely different character in a different part of town doing something else. And some of those stories overlap and some don’t, and some begin and end in a single scene. I’ve never seen anything as sophisticated as it on television before.

The show has very few sets, is mostly location shooting, with some locations barely dressed at all. That’s one of the pure genius moves of the production team, to put their actors in locations that look completely, absolutely normal, and, using nothing but camera movement and editing, make us dread every shadow and off-camera sound, because every single new piece of information we get could mean a miracle or instant death.

The weirdest part of all this is that Black Summer, like its parent show Z Nation, were produced by The Asylum, creators of Sharknado and ten million other “mockbusters,” cheap knockoffs of hit movies designed to confuse and entice the unwary content consumer, with titles like Transmorphers and Titanic II. How a piece of high art like Black Summer got through their development process, I have no idea.

Some thoughts on Elvis (2022)

I was dreading Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis. A long time ago, I had written my own Elvis project, and had done a deep dive into his life and work. I’ve watched a lot of Elvis-related movies (including all 33 of Elvis’s own movies), and the trailers for Luhrmann’s gonzo spectacle were a severe turn-off for me. But enough friends of mine had positive things to say about it that I thought I’d give it a chance.Almost immediately, I fell in love. I have lots and lots of quibbles about this and that, but the important thing is that Luhrmann’s understanding of Elvis, his art, his story, and his place in the American pantheon of great 20th-century artists, is the same as mine.Most people my age and younger experienced Elvis’s career backwards: when I was a child, Presley was a joke, a has-been, a bloated cartoon character adored by yokels and middle-aged women. He wore the gaudy jumpsuits and did his lame kung-fu moves, and recycled his ancient hits with blaring, Vegas arrangements that deprived the music of any of its original power. Elvis was sentimental, hollow and tasteless, and, when he died in 1977, it felt like more of a relief than a tragedy: at last, the empty, spangled parade float of his career was put out of its misery.Most of the movies made about Elvis begin with the same philosophy: start with the spectacle, never the art. In most Elvis projects, Elvis is a pawn, a wild animal, a naive wild card, a crazed lunatic, a wayward soul, a victim of greed, but never a serious artist. Luhrmann’s Elvis is the first project I’ve seen that actually takes Elvis serious as an artist, as a real, honest-to-goodness musician with a vision and artistic goals. It places Elvis in the context of his times, something that’s impossible to do when you start with his jumpsuits and drug use and work backwards.I had a number of misgivings about Austin Butler’s performance in the first hour or so of the movie, but all those doubts evaporated when it came time to the 1968 comeback special, where he not only was able to match (or at least approximate) Elvis’s incredible energy and handsomeness of that time, but also get across the very serious, very important artistic thrust of that show. Because while the show looks like old television to us now, it was absolutely a bolt from the blue in its time, a radical, bizarre, soulful and crucial turning point in Elvis’s career. And yes, Robert Kennedy really was killed while they were shooting the special, and yes, Col Tom really did have a heart attack when Elvis refused to sing Christmas songs in front of a fireplace. The emphasis the movie gives to the creation of that special is pitch-perfect, and the dramatization of events that led to Elvis singing “If I Can Dream,” along with Butler’s pantomime of Elvis’s performance of that number, had me sobbing for minutes on end. Not weeping, or choked up, but openly, audibly sobbing. Elvis’s message for the special was “I am still here, and still relevant,” and he thought it was vital that he close the show with some sort of statement on all the things that were happening in 1968. The fact that he chose “If I Can Dream” not only puts an exclamation point on the show, but also cements his point of view on the world. Everything that Elvis ever dreamed came true, a million times over, so if he could dream of a better world, why couldn’t that dream also come true? The answer is, of course, that Elvis was but a man, a mere singer (how ironic the show was sponsored by Singer), and had no power to shape current events. The repeated question, “why can’t this happen,” shows the song to be a prayer, both a pleading and an insistence. The repetition of the question reveals that the singer knows the answer but must still ask the question. Luhrmann’s movie gets across all that artistic turmoil without ever having to state any of it. The same goes for the construction of Elvis’s Vegas shows of 1969: while people my age were repulsed by the 1970s Elvis, Luhrmann’s movie places those decisions in context as well: as deliberate artistic choices made by a valid musical force who was looking for answers. He dressed like a superhero because he thought of himself as Captain Marvel (or Shazam, as he’s called now). (The lightning bolt from his TCB logo was lifted directly from Captain Marvel’s suit.) The splashy Vegas arrangements of ancient blues songs weren’t meant as a cheapening of an authentic musical form, they were meant to spread the message on the largest canvas available, and the movie brilliantly brings those decisions to life, drawing a direct line from Elvis overhearing Arthur Crudup sing “That’s All Right” in a Mississippi whorehouse to Elvis belting it out on the biggest stage in Vegas: not a cheapening, but, in Elvis’s eyes, an exaltation, a spreading of the gospel.As with any bio-pic, events are simplified and motivations are overstated. Luhrmann is, after all, the opposite of a subtle director. Overstatement is the water he swims in. If he wants to make a narrative point, he doesn’t just underline it, he underlines it, in italics, then draws a circle around it, then draws a bunch of arrows pointing to it, then states it again for the people who didn’t catch it the first five times. The difference between Luhrmann and, say, Oliver Stone, another director with a penchant for overstatement, is that Luhrmann understands cinematic narrative in a way that no other director does, and his bag of tricks is vast and endlessly malleable. He compresses time as all bio-pics do, but does it in a dazzling, fluid, exciting way, with tons of information going on all the time in every corner of the screen. His goal is to catch you up in the sheer giddy pleasure of images, over and over again, to get you drunk on the sheer spectacle of ideas unfolding. After seeing his Great Gatsby, I thought, well, that’s not the movie I would have made, but, well, it’s The Great Gatsby, you can’t look at it and say he betrayed the author. He didn’t destroy Fitzgerald, he just put it in neon. Just as Elvis turned the blues into a Vegas spectacle because he wanted to preach to the largest possible crowd, Luhrmann wanted to make sure that Gatsby, a fragile, tender, interior novel about sadness and regret, into a mind-blowing spectacle, because he truly loved the material and wanted people to see it.And, while I can’t say I fully understand what Tom Hanks is doing in the movie, with his bizarre accent and weird prosthetics, his Col Tom is, by far, the most humane, most nuanced portrayal of the old Mephistopheles I’ve ever seen. It still astonishes me that Col Tom referred to himself as “the king of the snowmen,” and had a banner hanging in his office advertising it. How many devils tell you to your face that they are a devil? Even Donald Trump didn’t say “vote for me, I’m a con man here to take your money.” And yet, Col Tom STARTED with that pitch. He introduced himself, advertised himself as a carny man, a man who literally spray-painted sparrows and sold them as canaries. When I wrote my Elvis musical (with incredible songs written by Chuck Montgomery, who also played Elvis), I could not explain in the time given why Col Tom had such a hold on Elvis, so I instead I made him a hypnotist. I gave him a jeweled-top cane that he used like Jafar’s staff in Aladdin. Luhrmann finally gives Col Tom an actual dramatization of his relationship with Elvis, showing him as both the father figure Elvis couldn’t find in his own father, a confidante who understood Elvis’s desperate need for attention, and, most importantly, a man whose only goal was profit. In the great American story of Elvis’s life, Col Tom is the vital component: the capitalist greed that destroys everything it touches.By the end of the movie I was an emotional wreck, not merely because the movie got so much right about the tragedy of Elvis, but because I was seeing a movie that I wish I’d been able to write.

107Shannon Sollman, Robert Sikoryak and 105 others36 Comments4 Shares

Halloween 2021

For my Halloween weekend viewing, I watched three low-budget midcentury grindhouse classics: Fiend Without a Face (1958), The Tingler (1959) and Carnival of Souls (1962). Watching all three, in that order, all in a short period of time, was both instructive and transformative, and reminded me that things like plot, performance and production value are not the only valid measurements of a movie’s quality.I’ve never been one to watch “bad” movies just to laugh at them, I’ve always figured that there are plenty of great movies to watch, why watch bad movies just to laugh at how bad they are? But now I watch flawed productions like these not to laugh at them but because they present cinematic ideas that, for a whole host of different circumstantial reasons, fall outside the mainstream. One can watch a movie like Fiend Without a Face and get plenty of enjoyment from it, just by looking at what the filmmakers were trying to do, and what they accomplished despite — or because of — the limitations of their budget and schedule (and talents). So, in effect, you’re watching two dramas unfold — one involving the characters onscreen and one involving the people making the movie. Through this lens, one can have a rich and rewarding viewing experience.I owe a lot of this understanding to the writer Brie Williams, who showed me Roger Corman’s A Bucket of Blood a few years ago. I’d always avoided Corman because he’s just not a very talented filmmaker, but A Bucket of Blood presented, to me, a new bargain in artistic terms. Corman said, in effect, “forgive me my total lack of production values and I will take your brain somewhere it’s never been before.” Since then, I’ve found that simply opening my mind to incorporate the circumstances of a film’s production into the narrative unfolding onscreen has brought me many hours of thrilling viewing. And it’s not just a question of being “in the know,” it’s a question of taking what’s presented onscreen and asking “Why is the camera there? Why is this scene lit like this? Why was this actor cast? Why does the director cut where he does?” and so forth. When you start asking questions like that, you start to be able to separate the ideas in the movie from the finished product, and get a sense of the challenges that presented themselves to the production, and a whole new meta-narrative unfolds.Fiend Without a Face (which is on the Criterion Channel) was an independent British production, made in England in an attempt to grab some of the American creature-feature horror market. Its plot centers around the delicate relations of an American air force base in a small Canadian town, and how those relations are strained by the sudden presence of mysterious brain parasites that may or may not be the result of the air force powering their base with a nuclear power plant. There is an A-plot about the people trying to solve the mystery of the invisible brain parasites, and then a B-plot about the politics of the shifting sands of paranoia in the small town by the base. The detective story is flaccid, but the political story is presented with comparative subtlety and complexity. For a movie about brain parasites, that is. Then, in Act III, the brain parasites become visible and lay siege to a house where all our main characters are trapped, while the protagonist attempts to solve the problem of the brain parasites by (checks notes) blowing up the nuclear plant. The third act is completely bonkers, with an army of oddly endearing stop-motion brain-monsters attacking the cast as the protagonist frantically scrambles to blow up the nuclear plant, saving the day and not creating a worse problem by blowing up the nuclear plant. The Tingler is directed by gimmick-master William Castle, and was a genuine studio picture (Columbia) with a still-low but appreciable budget of $400,000. Vincent Price is a scientist studying a, yes, brain parasite, which he calls “the Tingler,” which lives at the base of everyone’s spine and which is imperceptible until a person is frightened, at which point the parasite wraps itself around the spinal cord and applies pressure until the victim is dead. The movie was released in theaters with a gimmick where there were electric motors attached to certain seats in the movie theater, and during certain scenes the motors would activate, causing the seat to vibrate, freaking out whoever was sitting there. There were actors at screenings who screamed and pretended to faint, to be carried out by fake medical personnel.So here is a movie that owes its existence to a gimmick. It was a gimmick-first, production-values second production. And yet, it’s a studio picture, so it’s well shot and well-lit. Or, rather, it’s shot and lit according to the standards of low-budget horror of the day. And again, you see the limitations of talent butting up against the demands of the material, and the demands of the “typical” audience. You see the interests of the screenplay ram into the demands of the producer, and, above all, you see the performances try to make sense of it all. In the case of The Tingler, well, I’d never really understood the value of Vincent Price as an actor until I watched The Tingler directly after watching Fiend Without a Face. Both movies are ridiculous, but Price’s performance in The Tingler elevates the whole movie. He commits to the absurdity of the piece and never, ever talks down to the material or rolls his eyes or winks at the audience. He singlehandedly pulls the movie together and keeps all its elements balanced, even when the narrative breaks the fourth wall in the third act and the Tingler is let loose in the VERY THEATER YOU’RE IN NOW. The Tingler’s script is also 100% more propulsive and weird than Fiend Without a Face’s, with not one but two subplots about severely dysfunctional marriages, and a brilliant acid-trip horror sequence that is genuinely disturbing. When you stop and think about it, the whole movie is genuinely disturbing, especially when you get to the end and then rewind in your mind all the choices that the filmmakers made to make the ending arrive as it does. Like Fiend Without a Face, the third act of The Tingler is off-the-hook batshit insane, with plot points stacking up by the dozens as it careens to its conclusion.After those two, Carnival of Souls feels like a giant leap into sophistication. It’s the only one of the three that doesn’t need the “so bad it’s good” apology. It’s the work of a genuine visionary who, for whatever reason, never made another feature. Its director was a successful director of industrial films, who had risen to the top of that field and worked with some of the biggest names in the business, and parlayed his success into the making of this psychological thriller. When it bombed, he became discouraged and never made another feature, but his work on this movie announces the arrival of a director as talented and unique as Kubrick. And if you’ve ever seen Kubrick’s first two features, Fear and Desire and Killer’s Kiss, you know that they are cinematically ambitious but utterly lacking in production values, performance and narrative logic. Carnival of Souls is quite a bit better than those movies, and while there are aspects of it that fall short, again, the more the viewer thinks about it, the more unique and peculiar the movie becomes. The performances are oddly flat and creepy, but it comes off less as amateurism and more of a directorial choice. Same goes for camera placement, lighting and editing: the director knows what he’s doing, but what he’s doing is out of step with the rules of traditional Hollywood moviemaking.The movie is about a young woman who survives a car accident and begins to have vivid hallucinations. She sees a creepy man following her around and is drawn to an abandoned amusement park at the edge of town. Her life unravels in a manner reminiscent of Polanski’s later Repulsion (both movies are essentially gothic horror, about young women going crazy), and while the production values aren’t great, they’ve been chosen with care — that care, again, dependent on the limitations of budget and schedule.At the peak of the movie’s oddness is a fantastic sequence where the woman goes to a department store to buy a new dress. She takes the dress into the changing room, and when she comes out of the changing room she has seemingly become imperceptible. Suddenly she lives in a world of silence, and people around her cannot see or hear her. Horrified, she wanders out into the streets, where the sound slowly comes back and she becomes perceptible again. It’s a perfect example of how ideas can trump production values, as it sinks in that, from an outsider’s point of view, there was a woman who went into a changing room and then never came out, and who then suddenly reappeared later in a park nearby. That’s a horror concept right there, and there are no special effects required.I sometimes think that someone needs to publish a book about these kinds of movies, where it’s explicated that they’re not to be judged like traditional Hollywood movies, but instead need to be handled with a little more care, with less consumerism and more analysis. At one end of this extreme is Ed Wood, who had no talent whatsoever but had a boundless enthusiasm for filmmaking, and at the other extreme is something like The Shining, a big-budget studio picture that is, nevertheless, deeply weird and unconventional, with a lead performance that veers wildly from naturalism to screaming, eye-rolling insanity. (I’ve often said I would pay good money to see a cut of The Shining that’s made up of all of Nicholson’s “normal” takes.) Movies like Fiend Without a Face, The Tingler and Carnival of Souls need a curator who will explain to new audiences that they can be watched for something other than camp value.