Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl part 2

Act I of Curse begins with Elizabeth Swann making a kind of a wish, a wish that a handsome pirate might one day come and steal her away. A handsome boy wearing a pirate medallion shows up instead, and she transfers her wish onto him, making him a pirate in her mind, if not in his. Eight years later, a handsome pirate, Jack Sparrow, does indeed blow into town, and indeed makes gestures toward stealing Elizabeth away, but winds up in the pokey instead. A crew of actual pirates finally shows up at the end of the act, and they do in fact proceed to steal Elizabeth away, but now that Elizabeth sees the reality of piracy, the looting and pillaging and killing (this being Disney, no actual rape is shown, these pirates are manifestly chaste), she recoils, and as the act draws to a close partly regrets her wish. Curse, in one aspect, traces Elizabeth’s evolution from oppressed daughter to daring adventurer (before returning her safely to her father’s world). The following two movies draw the character out further, making Elizabeth “her own pirate,” as it were, before she finally outgrows the whole pirate thing and settles down.

Elizabeth’s goal is to awaken the pirate she knows to be in Will Turner, and so it is perhaps appropriate that Act II begins with Will literally waking up, the morning after the pirate raid, ready to fetch his love by any means necessary, including, we shall see, acts of piracy.

Will goes to Norrington and Governor Swann, pressing them to pursue Elizabeth. They are, of course, already going about that very business, but doing it in their bureaucratic, non-man way. Will slams his hatchet down on Norrington’s table (not a sword this time). Will proposes making a deal with Jack (prompted by the two British soldier clowns), but Norrington brushes Will, and his hatchet, aside. He informs Will (and us) that he knows that Will, with his expert sword-making skills, is in love with Elizabeth.

(Each “side” of the narrative gets two clowns. The pirate side gets Pintel and Ragetti, the British side gets Mullroy and Murrtog. The function of each clown duo is the same on each side: to deliver exposition to the principals, and the audience, in a humorous-enough way so that we don’t notice that it’s exposition.)

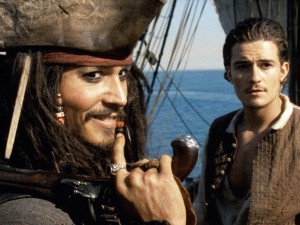

Thwarted, Will goes to Jack himself, to learn where the Black Pearl makes its berth. Jack, perhaps guessing Elizabeth’s goal, asks Will if he “wants to turn pirate.” Will refuses, but Jack agrees to help Will after he learns his name. This is another reminder about “Bootstrap Bill,” which, again, turns out to be crucial to the plot. Because “Bootstrap Bill” doesn’t actually appear in this movie, the screenwriters have to include as many references to him as they can so when they finally spring the Bootstrap Trap we won’t feel cheated. (Also in the jailbreak scene, Jack insists he cannot leave “without my affects.” This includes his hat, his compass, his sword and his gun. The hat and the sword have no narrative importance, but the compass and gun do, and the dialogue, and the shot that accompanies it, are inserted for similar reasons as the “Bootstrap Bill” reference — so that when the compass and gun are employed, the audience doesn’t say “Wait, he was put in jail and escaped and still has the same compass and gun?”

Jack and Will steal a ship, and their theft is a nice piece of sleight-of-hand. They commandeer one ship, the Dauntless, a ship they cannot possibly get out of the harbor, then, when that ship is boarded by the more impressive Interceptor, they jump the Dauntless ship and make off with the Interceptor.

Once they’re out on the open sea, Jack and Will have a long chat about “Bootstrap Bill,” Will’s father. Will painstakingly explains that he was raised by his mother and came to the Caribbean “to look for his father.” Jack informs Will that Bill was a pirate, which Will refuses to believe. Since we’ve never actually met Bootstrap Bill, his story means nothing to us — none of this information registers as important, except that Will, whether he likes it or not, is a pirate. It’s one thing to tell stories about an offscreen character, but to tell stories about an offscreen character we’ve never met before is much weaker.

Jack and Will sail into Tortuga, which is presented as an ur-Wild West town. They find Mr. Gibbs, who has apparently made the jump from sailor to drunk, although it’s not clear how he knows Jack.

Jack conspires with Gibbs to find a crew to take the Interceptor to find the Black Pearl. Jack carefully explains, for the second time in five minutes, that Will is the son of Bootstrap Bill, which, again, he must, as often as he can, since otherwise the forthcoming plot won’t make any sense.

Meanwhile, aboard the Black Pearl, Elizabeth is being offered, yes, another new dress, this time by Barbossa, who might now be seen as “the bad father.” Both Governor Swann and Barbossa want to put Elizabeth in dresses, and both offers are repellent to her. The inverse, however, that Elizabeth not wear anything at all, on a pirate ship, is a mocking reminder of her childhood wish to be taken by pirates. She’s got what she wanted now, and has gotten more than she bargained for.

Elizabeth dines with Barbossa, who explains to her the curse of the title. Here is a pirate story that’s not about stealing treasure, but returning it (like Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull), about forgiveness and redemption, and justice. How, exactly, Barbossa and his crew managed to gather up 882 pieces of gold I’m not sure (it’s a good thing none of it was melted down or put into a safe-deposit box), but Barbossa lays out the “rules” of the narrative: they have to return every last one of the 882 pieces of cursed gold, and also pay the “blood debt” that goes along with it.

Does that make any sense? No, it does not. It’s plot, pure and simple. What if Bootstrap Bill Turner had never had children? What if Bootstrap Bill Turner had children but they died in infancy, or during an ocean crossing (as young Will almost did)? Where would Barbossa and his crew be then? Why would they search the Caribbean looking for 882 pieces of gold when they have no idea if they’ll be able to find a relative of Bootstrap Bill as well? Because that’s what they need, not just the coin, but the coin in the possession of Bootstrap Bill’s offspring. What are the odds of that happening? (Excepting, I suppose, that Barbossa knows that Bootstrap Bill sent the one missing coin to his child, which at least gives him some hope of finding both in the same place. But if Barbossa knows that Bootstrap Bill sent the coin to his child, why does he not know that the child is a boy and not a girl? He’s surprised when Elizabeth tells him her name is Turner, as though perhaps this was merely a stroke of luck.

In any case, the audience quickly forgets about this nonsense because suddenly Elizabeth realizes that the Black Pearl is crewed by a bunch of SKELETON PIRATES.

You can only see that they are skeletons by moonlight. Why? No reason. There is no reason why Jack’s compass does what it does, there is no reason why Barbossa thinks he can find his missing coin and Bootstrap Bill’s child at the same time, and there’s no reason why the pirates appear to be skeletons in the moonlight, except that it looks cool.

The way that this goes is, the screenwriters get an idea (in this case, inspired by the theme-park ride): Hey, what if the pirates are actually skeletons? But then they decide they want to keep that as a surprise. How do they do that? By making up a rule. How do they make up a rule? They pick something that sounds lyrical and spooky — “Only the light of the moon shows them for what they truly are.” Will the audience by it? They will, if the rule is simple and makes lyrical and thematic sense. (Note, the cursed pirates must be direct moonlight — not even reflected moonlight, or diffuse moonlight, shows a thing.) The coin, the compass, the moon, all these arbitrary rules in Curse are there to simply advance the plot, to get the characters from one place to another so that they can keep crashing into each other in increasingly interesting ways. Elizabeth cannot get what she wants unless the coin is cursed and she steals it from Will and then lies about what her name is.

Now, the pirates of the Black Pearl present a definite physical threat to Elizabeth — but still not a sexual one, for obvious reasons.

Back on Tortuga, Jack has assembled his crew, including a woman named Anna Maria. Anna Maria, I’m guessing, was the owner of the boat that Jack sails into the harbor of Port Royal in.

Once at sea, in a storm, Mr. Gibbs explains to Will a little bit about Jack’s magic compass. The scene is there, I think, solely for this hint of exposition, and is set in a storm to provide “production values,” so that, again, we don’t notice so much that it’s exposition.

Elizabeth, in her new dress, is taken by Barbossa to the Isle de la Muerta to give back the gold coin and pay the blood debt. Jack, somehow, manages to get there seemingly minutes afterward. (The first act of Curse is a model of compact, efficient timeline — after that, time gets increasingly fuzzy. It seems like only two days have passed since the movie started, but that seems increasingly unlikely as the movie goes on.) Having told Will (and the audience) about Jack’s compass, Mr. Gibbs now helpfully goes on to explain about his gun. Jack’s gun, we are told, exists to kill Barbossa for mutinying against Jack back in the day. Having been told this, now we know why Jack had to go back for his gun, and why he told Will earlier “This shot is not meant for you,” and thus, we know that Jack will, ultimately, somehow, kill Barbossa with this one shot, improbable as all that seems. (Having explained the compass and the gun, Mr. Gibbs is then tasked with explaining how Jack supposedly got off the island where Barbossa left him. Mr. Gibbs is charged with a lot of heavy lifting in this movie.)

While Barbossa takes Elizabeth to return the gold and pay the blood debt (how does the gold know whose blood it is?), Jack and Will sneak onto the island and attempt, I guess, a rescue. (At least Will does — I’m not clear on what Jack’s expecting out of this particular caper.) Jack points out that Will is acting as a pirate, no matter how much he claims he is not, which puts him a good deal closer to becoming the man Elizabeth wants him to be.

Because Elizabeth is not Bootstrap Bill’s daughter, the “blood debt” doesn’t take. Sadly, Barbossa waits until after he’s brought his entire crew to the Isle de la Muerta, and performed the blood-debt ritual, before asking Elizabeth if she’s the child of Bootstrap Bill. Even more sadly, when he finds out she’s not, he slaps her and sends her, and the coin, flying, so that she can abscond with it, and Will.

Jack, knocked unconscious by Will, is captured by the crew of the Black Pearl and brought to Barbossa, while Will brings Elizabeth to the Interceptor. Will has fallen in with pirates and now betrayed the man who brought him to his goal, and is therefore now closer than ever to being the man Elizabeth wants him to be, and yet, even now, she is not content — something is not right.

Elizabeth’s journey from the beginning of the movie to the end of Act I is from the world of her father to the world of Barbossa. In Act II, she is taken to the heart of the world of Barbossa and rescued by Will. But she’s left something behind — not the medallion, but Jack, whose goal has nothing to do with Elizabeth or Will. Elizabeth, at the end of Act II, should have what she wants, but she — or rather Will — has made a crucial mistake, and now Jack, unpredictable Jack, is temporarily allied with Bad Father Barbossa.

(The 882nd Gold Piece is a powerful maguffin, but it occurs to me now that Elizabeth is, herself, almost a maguffin — the movie is about how she changes hands from Governor Swann to Commodore Norrington to Jack Sparrow to Captain Barbossa to Will to Jack again.)

(this being Disney, no actual rape is shown, these pirates are manifestly chaste),

Though the later threat that Elizabeth can dine with the crew sans clothes if she doesn’t put on the dress is edgier than I would have expected in a Disney movie.

————

One thing that struck me in those movies; the ghostly/skeletal pirates aren’t part of the Disney ride at all (Though it does have some resemblance to a train ride at the Cedar Point amusement park in Ohio, where you go through a frontier town full of skeletons: http://www.cplerr.com/cpg143/thumbnails.php?album=6 )

But it does bare some resemblance to the skeleton PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN plastic model dioramas from the 1970s.

Of which there used to a be a nifty webpage about, and it’s no longer there. Grrr.

But here’s one reference:

http://christiandivine.wordpress.com/2009/10/05/pirates-of-the-caribbean-with-zapaction/

I suspect the movies were as much inspired by these plastic model dioramas as the ride.

Oh, the skeletal pirates are very much part of the Disneyland ride — they’re the first thing you see after the plunge into darkness. Specifically, two skeletons speared by their swords on a beach, a skeleton crew on a ship’s deck in a storm, skeletons drinking and playing chess in the “crew’s quarters,” and a skeleton captain examining a map in a sumptuous bed, surrounded by treasure, all of which is alluded to, in parts, in the movie.

It’s interesting how the term “pirate” is thrown about like a racial epithet in this movie. People “turn pirate”; they “have pirate in [their] blood.” Pirates aren’t just “the people who commit the crime of piracy” – they have a particular attitude, a certain code, known hangouts, etc.

Weird. I went to Disneyworld in 1973, then again in 1998 or so, and to Disneyland in 1999, but somehow I just remember the fleshy pirates on the ride, not the skeletal ones.

In any event, that webpage that I was talking about that displayed the 7 MPC model kit dioramas from the 1970s (with Zap/Action!) has now moved here: http://www.yohoyoho.com/items/#hard_to_find

I’m going to have to watch this movie again, now that I’m looking back on it with new eyes. This whole paradigm of Elizabeth’s sexual “safety” is fascinating. The fact that the script goes out of its way to establish that she’s *not* going to get horribly raped by a ship full of horny pirates is especially interesting now. They’re literally impotent, the curse having stolen the ability to enjoy even the slightest pleasure of the flesh. I can’t help but wonder if there’s a deeper meaning or symbolism to the pirate’s impotence, though.

Jack is a walking pile of sex in contrast. But then again, we never see him succeed with anyone in the course of this movie until the very end, when Anna Marie (played by a then-unknown Zoe Saldana!) drapes a coat on his shoulders and silkily intones, “The Black Pearl is yours”, with a not-so-stuble “and so am I” left unspoken. Perhaps Jack’s quest in the movie has been to reclaim the Black Pearl as a correct symbol of pirate masculinity — in the hands of Barbossa, the Pearl degraded, but now that Jack has taken the ship back, he’s brought it (and himself) to full mast. Ahoy there, Dr. Freud!

The fact that the script goes out of its way to establish that she’s *not* going to get horribly raped by a ship full of horny pirates is especially interesting now. They’re literally impotent, the curse having stolen the ability to enjoy even the slightest pleasure of the flesh.

I don’t think it’s as reassuring as that. The implication I got is that they are physically capable of all sorts of pleasurable activity but don’t feel the pleasurable sensations.

“You can only see that they are skeletons by moonlight. Why? No reason. ”

“(how does the gold know whose blood it is?)”

MAGIC! Magic is the reason. Any child knows that. Those are perfectly acceptable magical conditions.

I understand that it’s magic, but how does it relate, specifically, to their condition? The gold was cursed by Aztec mystics, fine — but why would a condition of the curse be that the moonlight shows them to be rotting skeletons? And why, for that matter, would they be shown to be such? Is it a Dorian Gray situation, where the moonlight shows their inner corruption, or are they actually rotting skeletons?

I’m enjoying your examination of the movie (as usual), particularly the multiple modes (thematic meaning, narrative utility, etc.), but have some questions/thoughts (as usual):

First, you say that Sparrow’s sword has no narrative importance (granted), but is there a thematic importance to not wanting to leave without one’s sword? In part 1, you noted that Will’s hand-made (ahem) hard-on is given to/commandeered by Norrington; so maybe it makes some sense for Jack not to leave his potency behind for the British Navy (insert “rum, sodomy, and the lash” joke here)–although, this being goofy Jack, it’s no surprise that his potency isn’t very potent: when he stabs Barbossa at the end, not only is it ineffective, but Barbossa then stabs Jack with Jack’s own sword, which is, I suppose, the closest we’ll get to a family-friendly Disney villain telling someone to go fuck themselves.

Second, you haven’t commented on the “Bootstrap” part of Bill’s nickname, which seems interesting to me insofar as William “Boostrap Bill” Turner’s on-screen stand-in is Will, and what has Will had to do in the absence of a father but to lift himself by his own bootstraps. There’s something funny to me about this self-perpetuating process (William Turner boostraps himself into the role of William Turner bootstraps himself…), but what’s particularly funny/cruel to me is that, in the absence of a father, William can’t simply forge (ahem) any destiny for himself–he makes for himself the same life as his father. (I’m also looking ahead to the end of the third movie, with William Turner out to sea, coming back to visit–but not to live with–his wife and son.)

Lastly, your commentary about the logic of magic in this movie–arbitrary but precise, persnickety and not entirely foreseeable–seems like a fair description of parental authority. I mean, as a kid, you learn not to lie or you’ll be punished; but when the doctor manifestly lies about whether or not the needle will hurt, for some reason, the rules against lying don’t hold.

it was very interesting to read http://www.toddalcott.com

I want to quote your post in my blog. It can?

And you et an account on Twitter?

I would like to exchange links with your site http://www.toddalcott.com

Is this possible?